WALKABOUT IN WEREWOLF COUNTRY

By

James Morgan Ayres

Werewolves can only be killed by silver bullets. Everyone knows that. Right? I’ve never even seen a silver bullet, let alone owned one. But once I wished I did, when menaced by a nightmare creature during a moonstruck night in remote Italian mountains.

The Le Marche region runs along Italy’s east coast. The Adriatic’s turquoise waters wash its golden beaches. The Romans who flee here to escape the hoards of tourists that overrun their city each summer call the area “Tuscany without the tourists.” But the Romans don’t venture much more than a mile from the beaches. The mountains of the interior have little in common with tamed and tour bussed Tuscany.

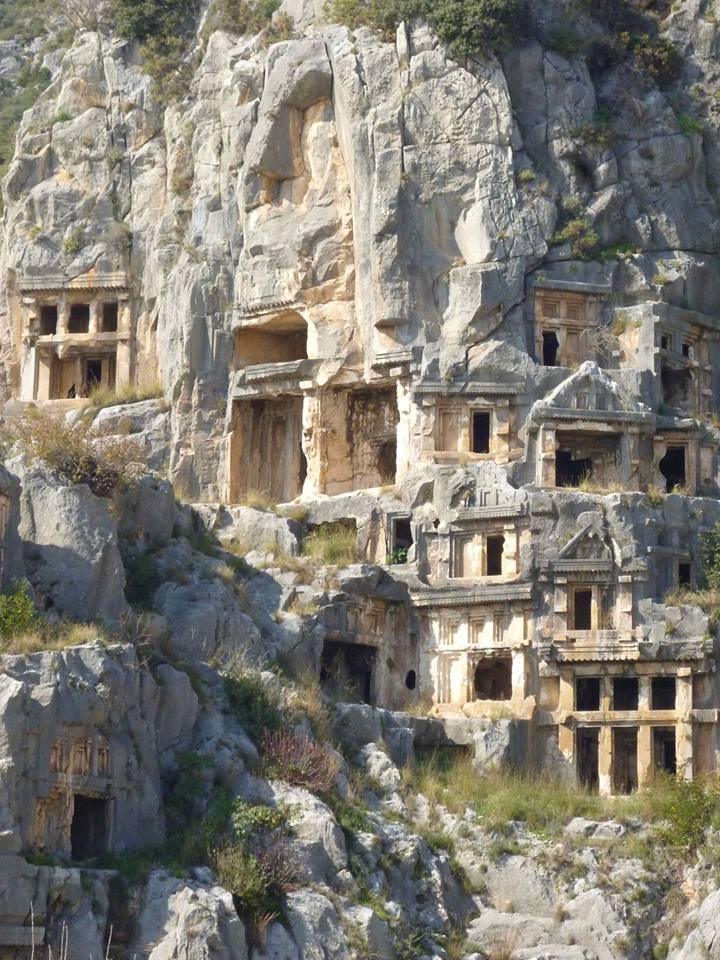

The Sibylline Mountains, part of the Apennine Range, straddle Le Marche. These remote hills and hidden valleys are wrapped in myth and legend. In the ancient world the oracle Sibyl lived in a mysterious cave in a mountain, which was named for her. Emperors and commoners came for her prophecies. Over the centuries the area became home to healers and herbalists, sorcerers who could call up storms, and, legend had it, werewolves.

Today Le Marche is still rumored to be home to wild magic. When I mentioned to one of my friends in Italy, an anthropologist, that we planned to do some foraging for wild edible plants during our walkabout in the Sibylline, she recounted a legend – that digging up a mandrake root without the proper invocations would cause powerful storms, wash away roads, flood valleys and send boulders tumbling down mountain sides. Mandrake roots could be safely taken from the earth only by a sorcerer and when accompanied by magical spells. She warned us to beware of anyone who had a mandrake root hanging over their door; these people were, perhaps, sorcerers – or maybe just crazy.

Regarding werewolves she said, “As an educated woman I must tell you that these are nothing more than creatures of folk tales. Although my father claimed to have seen one when he was a boy.”

“So you don’t believe in them?”

“Of course not. But…”

Before leaving home I did some research on the area’s fauna and learned that the Sibylline mountains were home to one of Europe largest populations of wild wolves with packs running free and taking down deer, sheep and sometimes cows. There had been no mention of werewolves in the biology text. Wild boars ran free in packs (herds?) snorting and snuffling through vineyards and gardens; they’re nuisances everywhere in the Marche hills, but probably not a menace. Still there seemed reason for caution.

I was in company with M.L., lovely wife and faithful companion of a hundred adventures, stalwart in emergencies and tolerant of my tendency to get us into…situations. The plan was to wander through the hills, mostly on foot and unencumbered by reservations. We were equipped for our journey with small rucksacks, a change of clothing and some simple camping gear. Our only defense against evil sorcerers and ravening predators a positive attitude and a corkscrew. I didn’t think we would really run into any bad tempered wild animals, shape changers or sorcerers but I was confident we would encounter more than one bottle of local wine. It was against this eventuality that I packed the all-important corkscrew. Hardly a weapon, but I figured if nothing else availed I could pull a cork and offer a glass of vino to potential assailants, two or four legged. Certainly Italian werewolves would welcome a nice glass of Montepulciano, sorcerers too. I’m sure of it.

Suitably outfitted for our adventure and setting aside our friend’s warnings we hit the road, planning to camp out most nights and stay in country inns every few days. Things didn’t turn out quite that way.

Our routine was to rise in the cool of the morning and trek intrepidly through the hills for, oh, at least an hour or two and lay up in the shade during the sun heated hours. No point in over exertion. One day, overcome by the beauty of the hills with their covering of umber wheat and olive trees with leaves fluttering in mountain winds and the heady scent of wine sweet grapes growing in rows next to the road, we forgot ourselves and pressed on through the afternoon. Throwing common sense to the wind and drawing on nonexistent physical conditioning we must have covered as much as five miles that day, maybe even six. But that was an exceptional day. Usually we strolled, stopping to examine ancient ruins, dangle our feet in cool running streams, talk to farmers, lie on our backs and watch clouds. Fresh greens and herbs for salads grew wild on the margins of fields, uncultivated fig and plum trees flourished.

When we wearied of our arduous pace we hopped on a local bus or simply raised a hand for a ride when a vehicle passed by – the friendly locals would find room for us even in tiny Fiats – wandering from stone village to tumble down Roman theaters, to medieval palaces and windswept mountaintops. Every village had a well-tended memorial to its fallen soldiers from the World Wars, and a café. Older folks had stories about American soldiers in War II, how they had welcomed their arrival and hid them from the Nazis and Fascists. One village square had been a POW camp for captured American soldiers and downed flyers. Italians had administered the camp and somehow the American prisoners had managed to meet local girls. After the war there were many marriages, and Italian American babies.

In early evening, after dawdling along a country road picking fruit and flowers, we would approach a farmhouse to ask if we could camp at the edge of their fields, a perfectly normal request and acceptable in every European country. Sometimes it was difficult to approach the farmhouses due to guard dogs, howling, slavering mongrels of uncertain ancestry and fierce disposition straining at their chains and displaying a heartfelt desire to tear us limb from limb.

Until M.L. smiled at them, and told them what good dogs they were, what a good job they were doing guarding the homestead, and asked them if they would they like her to pet them. They invariably did, rolling over in helpless adoration to have their bellies rubbed, or nuzzling her knee to have their ears scratched. This happens the world over. M.L. has some kind of dog magic; it works on cats and horses too. Now you see my strategy. It was M.L. and her critter magic that was our first line of defense against fierce creatures. I wasn’t sure her powers would work with werewolves but was willing to give it a try.

While the dog seduction was taking place householders would come outside to inspect the intruders and we would say hello, introduce ourselves and ask for a spot for our tiny tent in the corner of a field. No one wanted us to camp in their fields. Everyone insisted that we stay in their homes and take dinner with them and sample the local wine and meet the family. In weeks of travel we never met a sorcerer or an unfriendly Italian, or English person. Le Marche is home to a scattering of expat Brits, all of them hospitable and good for great conversation and much fun.

One evening we stopped in the overgrown grounds of an abandoned farm to watch the setting sun set the sky aflame and decided to stay the night. We wanted to be alone and out of doors and to watch the moon come up and the stars blink on. As the color faded from the sky, M.L. sliced a thin loaf of bread, and tomatoes plucked from a roadside garden and smelling the way tomatoes smelled when you were a kid. We had prosciutto and soft cheese, a salad of foraged greens dressed with olive oil and balsamic. The figs from a tree at the edge of a fallow field went with a nice bottle of Sangovese from my pack. The moon lighted our campsite as we spread our sleeping bag. It was too warm to bother with the tent. Night wind flowed down the hill, passing over a stream and bringing the scent of water over stone.

I awakened during the night to the sound of rustling in the bushes at the edge of the clearing around the house. The full moon sat on the horizon and cast deep shadows as mist rose from the valley below. The noise from the brush grew louder. I was a little foggy from the Sangovese. And there had been that shot or two of Grappa after dinner. Well, maybe three. Who counts? Anyway, I was pretty sure I saw a flash of fangs in the moonlight. Could this be the creature of legend and nightmares?

A low growling came from the bushes. M.L. wakes up and says, “What’s that noise?”

“Probably a werewolf.”

“Right,” she says, turning over to go back to sleep.

Then I see it: a dark shape, fangs definitely flashing in the moonlight. The creature throws back its head and howls, a long, wavering wail that sends chills up my back. A werewolf for sure. Now I’m wishing for that silver bullet and a pistol – the corkscrew totally forgotten.

M.L., hearing the blood-curdling cry, sits up quickly and peers at the bushes, “Here puppy,” she says. A whine comes from the bushes. “Oh come on, come over here.”

A monster the size of a Fiat 500 slinks out of the shadows. Revealed in moonlight, it looks like a cross between a timber wolf and a Tasmanian Devil. Hair bristles on its back. Its tongue lolls from its slavering muzzle. The beast stalks slowly towards us. It could pounce any second. I ready myself for a fight to the death.

“There’s a nice doggie,” M.L. says. “Are you hungry? Want some water?”

Doggie? The brute licks her hand and, of course, rolls over on its back for a belly rub. M.L. gets up and pours water into our single pot, which the animal laps up while gazing worshipfully at her. She digs out our salami, prosciutto and bread, all of which the creature gobbles up with those fangs (yes, I was focused on those dagger like fangs) while M.L. keeps up a patter, “Poor puppy, so hungry, you’re such a good dog, and so handsome too, are you lost, have some more prosciutto, do you like salami?”

Me? I’m still wishing for that silver bullet. Finally the love fest is over and M.L. gets back in our sleeping bag. The “poor puppy,” snuffles around for a while then lies down at our feet and goes to sleep. I doze off to the sound of its snoring, aware that the creature could turn savage and go for our throats in the night. But hey, it’s late and I’m tired.

We awakened with sunlight on our faces. Our nighttime visitor had disappeared. Probably hiding from the sun, or returned to human form, as werewolves do. We packed up our gear and strolled to a hilltop village in search of coffee. On the way to the café we stopped in a butcher shop for more salami. Of course the beast liked salami, ate the last scrap. The butcher plied his trade in the traditional way: making his salami to a family recipe, seasoning it with wild herbs he grew on the hill behind his shop.

Over steaming cappuccino and fresh rolls on a café terrace overlooking Mount Sibyllini I reminded M.L. of our assignment to cover a trade show at the other end of Italy. Duty called. We should leave the hills and catch a train. Find a hotel that wouldn’t require a second mortgage to pay for a room. Call on the Chamber of Commerce. Arrange interviews. Make notes and take photos. Do things. Work.

“We really should go to work,” M.L. said.

On the other hand.

“There might be a sorcerer who can call up storms in the next valley,” I said. “The one over that mountain,” pointing to snow capped Sibyllini. “Maybe we could find Sybil’s cave. There could be a werewolf over there. That would be a story. You could get photos.”

M.L. looked at the beckoning mountain and set down her cup.

“Let’s go,” she said.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

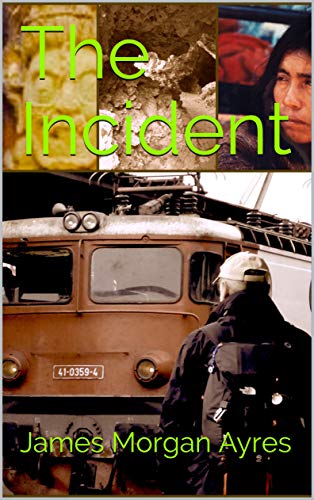

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End