Thiers, a mountain town deep in the green heart of France.

Thiers, a mountain town deep in the green heart of France.THE THIN BLUE LINE

By

James Ayres

The TGV train travels at about 200 kilometers an hour. The rolling hills south of Paris flashed by. The skies were gray with looming clouds. The train had soft seats and hot coffee and it was good to just sit and watch the world go by, and think of the green hills and sunshine in the beckoning south.

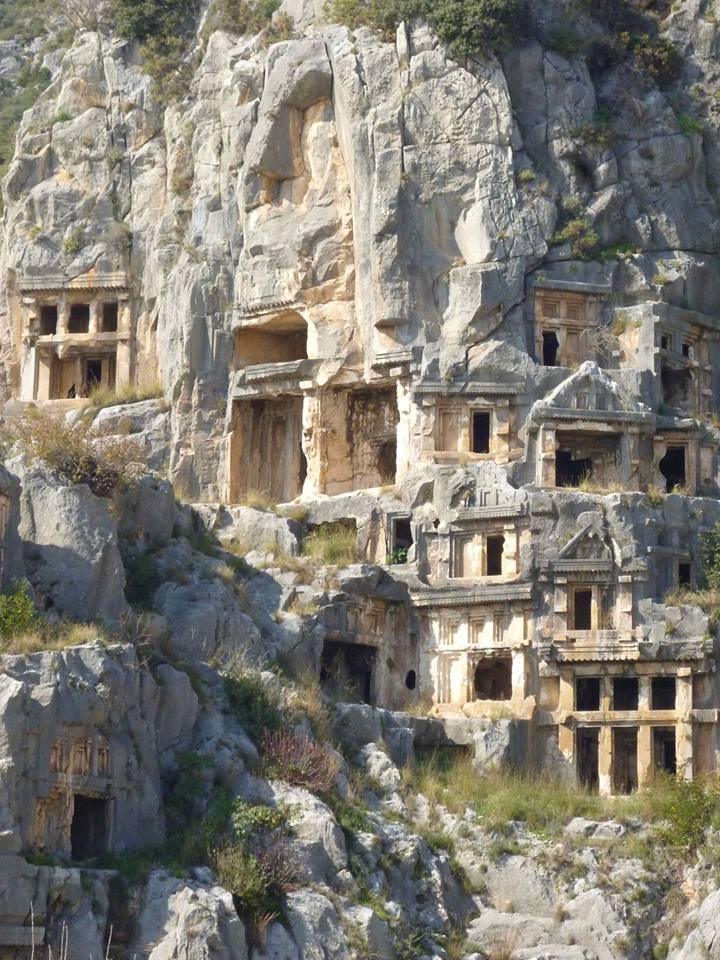

I had been in Holland on business – too many days of smoky rooms and talk, talk. Now I was finished with all that and headed for Thiers, an ancient mountain town, and the famed capitol of artisan knife making in France. I had visited Thiers three or four times during the past few years and each time met new friends and learned a fair amount about how the French approach the craft of knife making

The French knife designer is conscious of his patrimony. He comes from a tradition of knife making that was old before our two countries were born. When he starts a new design he considers how to evolve from hallowed tradition, how to create something fresh while respecting all that has gone before.

I arrived late in Lyon, where I rented a car and drove directly to the Moulin Blu, a wonderful country hotel, where I always stay in Thiers. The next morning after an omelet, and hot frothy café au lait I drove narrow streets past buildings leaning on each other like tired old men, to an address high on the mountain above the town center. After parking my tiny rental car I crossed an ancient cobblestone street and pounded on a green steel door in a stone building that probably was built about the time George Washington crossed the Delaware.

Gilles Steinberg, the owner of Fontenille Pataud, greeted me with a smile and the rough handshake of a craftsman who still works on the bench. Gilles, a tall man with a bushy mustache, led me into his workshop, a rambling place of many high ceilinged rooms filled with old machinery and heavy antique furniture. Five or six men, most wearing “blu de travail” jackets and pants – the traditional blue denim work clothing of the French working man – were grinding, buffing, filing, and polishing folding knives.

No two knives were alike. Some had elaborately engraved silver handles; others had handles of polished olive wood, walrus ivory or buffalo horn. Blade steels included Damascus, carbon steel, and modern alloys. Most were engraved or had fancy file work on the spines. There were minor variations in blade shape but all were the pattern of the Laguiole. Fontenille Pataud makes other patterns, but on that day it was the Laguiole knife that was in work. Gilles said that the Laguiole accounts for a considerable amount of his production.

The Laguiole is a folding knife with a couple of centuries of history. The blade is a long graceful clip, similar to the Najava and has a lock notch, post and strong spring that keeps it from closing on your hand during normal use. At the joint of blade and handle there is always a carving of a bee, or a fly, stories vary regarding this point. Most Laguioles are single bladed, but some show their heritage as a shepherd’s knife, with the inclusion of a long, slim, needle sharp punch. Many have another essential tool: a corkscrew.

All true Laguioles have a pattern of nail heads on the scales arranged in the form of a cross. As late as the last century shepherds would be away from home for months at a time in order to pasture their flock where grass was plentiful. The roving shepherds traveled by foot and carried little. Their only tool was this humble folder, which they used for daily tasks and to perform certain kinds of surgery on their sheep.

Since the shepherds carried no calendar and a watch would have been an unthinkable expense they also used their knife to cut notches in a stick to count the passing of the days. On Sunday the solitary shepherd in his high and lonely meadow, would open his knife and plunge the blade into the earth, so that the cross was in front of him as he knelt and prayed, the sky his church, the tiny cross his altar.

Today there are few, if any, nomadic shepherds, and certainly none who live as in the past. But The French retain great affection for this romantic and still useful folder. Thiers makes hundreds of thousands a year and Gilles workshop accounts for the production of a small percentage of the very best custom versions.

I talked with Gilles in his office. A large wooden table served as his desk. Amid all the old furniture, knives and bits of knives scattered on his desk, was the latest generation computer with broadband connection. He told me about the changes that had been affecting Thiers.

“ The low cost competition from China has almost destroyed the part of the French knife industry that produced inexpensive knives. There is no more market for the kitchen knives that were produced here in the millions and which kept knife factories in business. China can produce anything we can make cheaper”

“How does this affect your business,” I asked?

“Well, not so much. My business is only in the custom market. I work to order and produce one of a kind and limited production knives only. I could see the direction trade was going and I knew I would have to specialize in order to survive. Besides, I’m a craftsman at heart love to make beautiful things.”

From Gilles office window I could see Puy du Dome, the dormant volcano that dominates the landscape hereabouts for a hundred miles. The sunlight streaming through his window had that spare thin quality that the winter sun sometimes has in places where the sky and air is as clean as it was two hundred years ago, before the industrial revolution, before the cascade of consumer goods that defines and delimits our lives, back when a knife was a prized possession, something that once acquired would be cared for, polished, kept sharp, and passed on to a son.

Gilles and his men go to work each day in this clear light. They forge and grind and polish steel and take pride in their work. French industry, like American industry, is inundated with wave after wave of cheap imports from the China, from factories where people labor eighteen hours a day for their bowl of rice. But Gilles has found a way to keep his business, his way of life, his men and their families alive. He has found that there remains a market for craft, for art, for the true commitment to creative custom work that no factory can duplicate.

His entire production line consists of six or eight men who daily mold steel into art. This thin blue line of work scarred men hold firm against the forces of globalization and keep their way of life intact by bending to their tasks and putting their blood and soul into their work. These men are much like American workingmen. Both face the threats of globalization. Both have been betrayed by duplicitous, greedy politicians, and both solider on the face of adversity.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

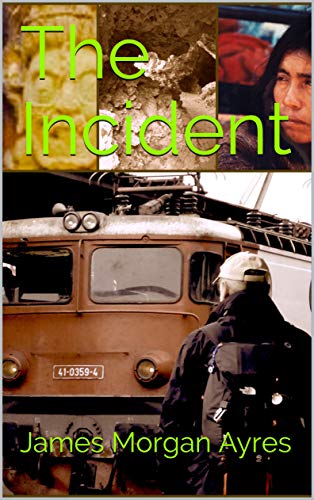

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End