And the giant is enchanting to Jack,

And the lily-white Boy is a Roarer,

And Jill goes down on her back.

– W.H. Auden

Prologue

They killed the parish priest on the altar at St. Michael’s during the hours of darkness. A radiant gold medallion was central to the ritual his killers called a sacrifice and communion. His death was prolonged and intricate and left the scattered white roses spotted red. While the priest was in agony and being separated from his body the young senator was murdered with a few shots from a small caliber revolver. The method of the senator’s death was simple and obvious, but the motive obscure, hidden behind layers of lies, curtains of deceit, a mountain of disinformation.

The old priest had been much loved and was mourned by his parishioners, and by his fellow soldiers in an ancient secret society, only they knew the reason behind his horrifying death. The police and the public were mystified. Millions mourned the young senator. No one mourned the third man who died that night. In life the three men had not known each other. In death they were bound together, their lives taken at the direction of a man who believed he was a god.

I’m in a shabby room in a cheap motel on lower La Cienega. The television had been on when I slipped the lock and slid inside, commercials, a stupid game show. The light from the bathroom spills onto the orange shag carpet. The windows are open. Hot summer night, a raspy desert wind, moths battering themselves on the screens, smell of Lysol. The phone rings once, stops. I pick it up the next time it rings and wait.

“Priest?” Covington asks.

“Yeah.”

“They stopped in a bar. Hang tight.”

Taylor Covington likes to sound like a tough guy. He isn’t one. He is a world-class liar, a professional requirement for a case officer.

The noise level on the television goes up, a roomful of panicked people crying, shoving. An interviewer shoves a microphone in a young woman’s face.

“She was wearing a dress with polka dots and he was in a double breasted suit.”

“What did she say,” the TV guy asks.

“She was laughing. She said, ‘We got him.’ ”

My chest goes hollow, as if the unseen hand of a thief had suddenly stolen my heart. The mission had felt wrong from the beginning. The phone rings three times and stops. A big engined car rumbles into the parking lot. Well, here I am, wrong or right.

I move to the side of a window. The Shelby Mustang swings into the parking space in front of the room. Streetlight falls on a broad-leafed palm and throws jagged shadows across the hood. A lush looking woman gets out on the passenger side. The skirt of her polka dotted dress slides up revealing smooth white thighs.

She’s walking towards the door of the room where I stand in the shadows with my handgun held down along my leg, her spike heels tapping, pulling a grinning man by the hand. A key turns the lock. The door swings open and the man in the double-breasted suit follows the woman into the room. They’re laughing.

He sees me and pulls her in front of him and comes out with a small revolver and everything is moving and it’s too late for talk and I drop him with two rounds to the bridge of his nose and he goes down like water poured from a glass. The new silencer works fine.

The woman freezes, looks at me, at the man on the floor behind her, at the television still on the scene at the Ambassador. She doesn’t scream or start flapping around.

“We…”

“Don’t speak. Drop your purse on the floor. Go to the corner. Put your hands on the wall. Don’t turn around.”

One handed I open the cylinder of his revolver dump the ammo on the floor and toss the handgun under the bed. No gun in her purse. I don’t want to get shot in the back. I go to her.

“Stand still. I’m not going to violate you.”

I run my left hand everywhere over her body keeping my automatic pointed at the back of her head. She’s sweating and trembling, breathing hard, smells of whiskey and cigarette smoke. No gun.

“Touch the corner with your nose. Stay there until I’m gone. You move I drop you.”

They’re out there now. I can feel them and their intentions. One of them could have a sight picture on the door, maybe a shooter with a rifle and a spotter in the office building across the street. Anyone in the unit could make that shot. Could be a team covering the entire area. Maybe two guys with Swedish Ks out back. A dry rattling sound comes from outside the window. Is someone there? No. It’s only wind in the palms, or rats. I read that the palm trees in L.A. have rats living in them. Figures.

No reason to wait. It’s not going to get any better. She has her face in the corner, her hands making sweat marks on the wall. I get the keys to the Shelby out of his jacket, the carpet now changing colors where it’s wet. I go out fast and low and in through the driver’s door slinging my shoulder bag to the side and jamming the key in and the Shelby’s engine roars and I’m in the street running hard.

The edge of my eye catches a young prostitute on the corner, wig like a Santa Monica sunset, chrome yellow skirt so short it barely covers her bottom, long chocolate legs, big injured eyes trying to believe it’s somehow going to be all right. She too was once a virgin, maybe is one still, in her heart.

Four of them are in a sedan near the corner and I’m firing out the window before they can get started, screeching tires, yelling, my slide locks back, blood on their windshield. I turn off the wide boulevard and head north through a neighborhood of small bungalows, televisions flickering through screen doors, screaming down the residential street at seventy and hating myself for the speed. Innocents could be strolling in the dimly lighted streets. Night air rushes through the open window carrying traces of half burned hydrocarbons, scorched rubber and cordite.

I hit the curved onramp doing eighty, tires howling and the Mustang fighting me like a wild animal until I burst out onto the 10 heading west. Below the freeway, city lights twinkle with empty promise. I kick the beast up to a hundred, watch my mirror and blow by a few long haul truckers and a scattering of slow moving cars. No tags. I slow to seventy scan for cops and swing onto the 405 south. Clear. For now.

I crossed into Mexico a few hours after midnight. On maps the border between Mexico and the United States is drawn by the Rio Grande, but I didn’t see any water when I crossed over, only concrete barriers washed in harsh light and men with guns.

Tijuana’s night streets were jammed with reeling gringo drunks and predatory cops. I cruised slowly away from the raucous crowds and through poorly lighted streets until I found a small industrial zone and parked in the shadows behind a rundown body shop. I dozed in the Mustang for a couple of jittery hours. When the shop opened I had the Mustang painted flat grey, covering the distinctive white paint job and blue racing stripes. The guys who painted it sold me some Mexican license plates from a wreck.

When they finished it looked like an ordinary Mustang, unless you looked closely at the wheels and the hood latches. South of TJ and past the last frontier check I punched the pedal to the floor and flew along a blacktop ribbon at a hundred and thirty.

I didn’t know where I was going. I was just running. I dropped a couple of black beauties and let the road take me, flying through frigid desert nights and scorched days, stopping only for gas and coffee, then speeding on fueled by caffeine and amphetamine. Hermosillo, Guaymas, Mazatlan, and a hundred dusty villages blurred by my windows, images from a fever dream. In the middle of one high-velocity night the radio caught an atmospheric skip, one of those megawatt stations pumping out the Stones:

I see a red door and I want it painted black

No colors anymore I want them to turn black

I see the girls walk by dressed in their summer clothes

I have to turn my head until my darkness goes

Got that right. I slowed when the drugs started wearing off and I saw things jumping into my headlights. The road pulled me into the pine-shrouded mountains of Michoacán, a hidden fastness of cold lakes and silent Indians. I stopped at a small hotel near Lake Pasquero, white walls, winding stairs, red tile floors.

My hands were trembling and my mouth full of cotton. I’d been awake for four or five days and had the shakes bad. Shadows were moving in on me. The desk clerk watched me from the corners of his eyes. Was he Covington’s? Covington had people in place from L.A. to Tierra del Fuego. Should I drop him before he could make his move? Paranoia striking deep. I dumped the rest of the black beauties Covington had given me for the mission down the drain. I had enough real enemies.

The nights brought fragmented dreams: his suddenly empty eyes and boneless drop, the mortal fear in the woman’s face. They were the bringers of death and she had thought they were therefore inviolate. She didn’t think that anymore.

I sweated it out for three days. No new guests checked in. They couldn’t possibly know where I was. I relaxed a little. The hotel reminded me of an inn in the Spanish Pyrenees where I had lived a month with a dark eyed girl who said she loved me. My room had a small fireplace and each night I shaved kindling for the evening fire with a horn handled French pocketknife. The knife had a slender blade and a corkscrew on the back. When I used it I remembered a night in the Spanish hills when I pulled the cork from a bottle of red, red wine and my dark eyed girl laughed and hugged me when the cork made a tiny pop.

But Michoacán was not Spain and there was no laughing girl. There were only dark hills hinting at hidden violence and occult ceremonies, and a young Indian woman who came each evening with fresh cut pine for the fire and cut her eyes slantways at me as she slipped out of the room. She never spoke, not even to tell me her name. Not even when she returned in the night, tapped at my door and slipped into my bed, all hot smooth skin and firelight casting moving shadows on her face.

One night drifting and dreaming in front of the fire I remembered Raphael, a friend who lived in Mexico City. And so, without much thought, I left the misty hills and dropped down into the brassy light of Mexico City. There, unwittingly, I laid the foundation for the tragedy yet to come.

But maybe it didn’t start in Mexico City. Maybe it started in a café in Paris, or a Special Forces training camp in Guatemala, or a cheap motel in Los Angeles. Maybe it started when I crossed the border, an invisible line on the earth but one marked in blood.

The happy rich people and their parties with flowing champagne and beautiful music were part of it. Kate and Elizabeth and the passions that bound us together became part of it. The gold medallion Raphael and I found in a temple undisturbed for centuries in the Yucatán jungle was certainly part of it, the part that led us on in search of ancient mysteries and to the discovery of true evil and the purposes of the cursed and obscene soul catchers. Maybe it started in Oaxaca. After Oaxaca there was no turning back.

De tanto andar una region

Que no figuraba en los libros

Me acostumbre a las tierras tercas

From so often traveling in a region

Not charted in books

I grew accustomed to stubborn lands

– Pablo Neruda

Chapter One

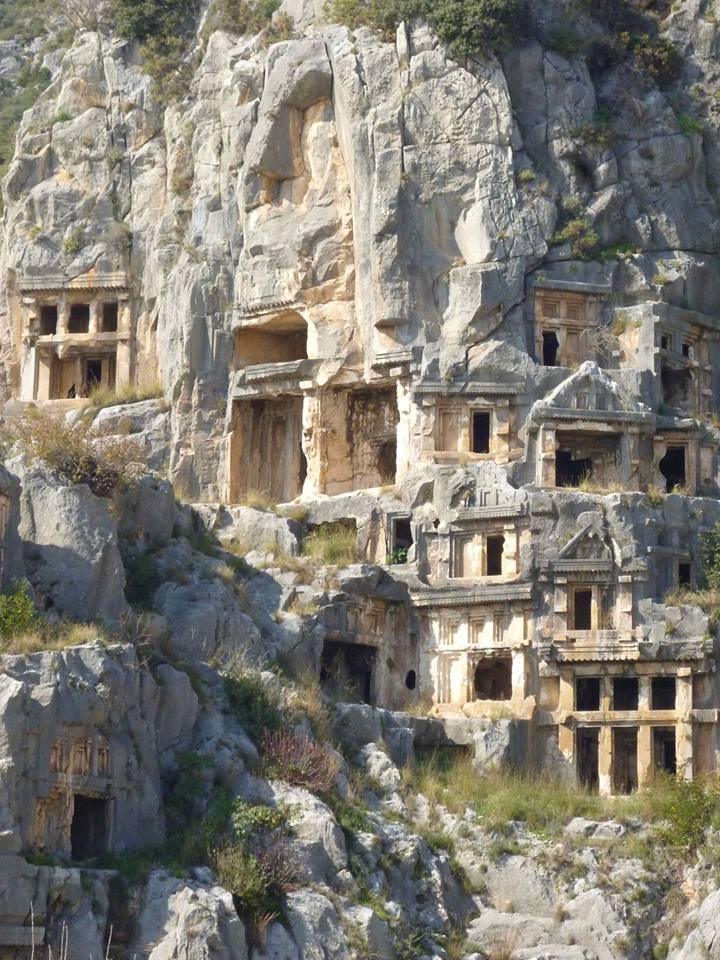

It glowed with the radiance of pure gold and smelled of death. A jolt of electricity ran through my arm when I took the medallion from its carved cavity under the capstone of the small pyramid. I heard screams and smelled smoke, felt waves of pain and terror and saw a man with golden skin, a fantastic feathered headdress and an obsidian dagger. And another man stretched naked over a stone altar. Then it was again simply a gold medallion and I was kneeling on the pyramid with my diggers.

“Que maravilloso,” Emiliano said, weighing the gold piece in his hand. His face fell and he tossed the gold piece back to me as if it was on fire.

“What?” I asked.

“Put it back.” Emiliano moved away from me.

“Did you see something too?”

Emiliano looked at me as if I was possessed, “See what? You saw something?”

Terrific. Now I was in a movie: the intrepid explorer finds a treasure and his faithful Indian guide freaks out. Except that Emiliano wasn’t a faithful guide. He was a levelheaded Zapotec businessman and my excavation partner. And I was more flipped out than he was. That vision, or whatever it was, took me too close to the edge.

“Let’s get out of here,” I said.

Emiliano calmed down and got his guys back to work. He was a serious man with black inquisitive eyes, sharp features, and a quiet, confident way of dealing with people. His men, three other Zapotecs, followed his direction without dissension. They levered the capstone back in place, working quickly, looking over their shoulders. I wrapped the gold piece in an old denim shirt and stuffed it in the bottom of my rucksack cushioned by a tattered paperback copy of Beowulf.

Dusk was creeping up from the valleys below and we wanted to be on our way before they came. Someone, or something, had been stalking us since I had found the overgrown pyramid three days ago in this hidden fold in a range of rugged dry mountains. Nights had been filled with moving shadows and rustling sounds in the sparse brush. Each night I had let our tiny fire die out, and while the others slept wrapped in their serapes I silently patrolled the area around our excavation. I saw nothing. Each morning I examined the ground for tracks. I found only our own.

Sometimes I dream true dreams. Dreams that, in a shadowy fragmented way, foretell. Last night I had dreamed of a snake the size of a giant python with glittering anthracite scales, slithering at the edge of vision, disappearing when I turned to see it more clearly, reappearing at the corner of my eye when I looked away. The creature circled the pyramid, coiling its way from the base to the top. On the peak it rose up in the classic pose of the striking serpent with curved neck and forked tongue. Its eyes shone like poisoned rubies and trapped me with hypnotic terror, a gopher before a rattlesnake.

Then I was awake, heart pounding. The night was still, first light a pallid glow on far mountaintops. Nothing menaced us in our little circle around a burnt out fire, nothing that could be seen. There was something loathsome about the dream serpent. It sent bone deep shivers of fear through my dream self. I had no idea what the dream foretold; only that it had the resonance of reality.

Emiliano and his men had tossed and muttered in their sleep and during the day cast furtive glances over their shoulders. The men had wanted to abandon the site. But Emiliano cajoled and shamed them into continuing. I had been drawn to this place. I had felt that there was another gold medallion under that capstone and I wanted it. Now I had it and it was time to go.

I snapped a few final photos of the excavation grid and the pyramid. Professor Mendoza would be pleased. We packed our gear as the sun sank into serrated ridges falling away to the horizon. With one of the men leading the donkey we walked through the moonlit night, down narrow rocky trails to lower country. Emiliano believed we were being watched by a brujo, a sorcerer.

According to the Indians there were sorcerers in these mountains who could fly on night winds, leave their bodies and travel through the underworld and cast spells to take a man’s life. After the past few days I couldn’t say the Indians were wrong.

Before I found the pyramid we had spent two nights in a small adobe village whose alcalde—mayor—extended his hospitality with manners as refined as any Washington D.C. diplomat. Don Cornelio was no more than five feet tall, with a narrow wrinkled face and a mischievous smile. His white shirt and shiny black shoes marked a man of means among the Zapotec and Mixtec.

The second day at dusk I had seen Don Cornelio leap from a cliff and fall a hundred feet into a canyon before disappearing behind treetops. Moments later an enormous raven flew cawing from the trees. At least I think that’s what I saw. I had refused the mushrooms the Indians offered. I smoked no dope whatsoever and had only one cup of what the Indians said was mescal, a thin green tasting local brew. According to Emiliano, Don Cornelio was a feared brujo and had killed over a dozen people with sorcery.

Until the past week I had blissfully wandered through open markets in mountaintop villages surrounded by crowds of Indians who had been trading in these markets for a thousand years, small people no taller than my shoulder. I became part of the color, and the resiny smell of burning copal incense, the smoke from meat cooking on open fires, the music of wooden flutes, thin notes drifting on mountain winds. I imagined that I could have settled down with one of the young women and forgotten how to speak English. These villages were all but forgotten by the Mexican government. Perhaps my own government would forget about me.

The moon rose full and pale as we wound our way down. The feeling of oppression lifted with each mile. We reached Emiliano’s village in one of those chill night hours when sounds carry, soft footsteps of a mouse in the cactus fence bordering Emiliano’s property, skittering leaves blown by dry winds, an owl’s wings making that fluttering sound that terrifies the small creatures of the night. I rolled out my serape and using my rucksack as a pillow made my bed against an adobe wall.

Emiliano had thought I was insane the first time I had insisted on sleeping outside. The night was filled with roaming spirits seeking to steal the souls of the unwary. He finally accepted that I preferred fresh air to be being closed up in a house with the shutters and door barred and that the night held no fears for me.

The serpent came again in my dreams, his coils encircling me, squeezing the breath from my chest. I awakened gasping for air and grabbing for my handgun. There was no serpent I could see. It was the last hour before dawn and nothing moved in Emiliano’s dusty yard. In the distance a coyote howled, the sky blue black, a single star hanging over a lone pine on a distant ridge.

Chapter Two

We ate breakfast quickly, beans eggs and tortillas. Emiliano wanted the gold piece out of his house. I wandered down the dusty main street. Cool morning air carried the smells of a Mexican village: donkeys, tortillas, wood smoke.

The pickup truck stopped at the end of the dirt road, or the beginning, depending on your direction of travel and state of mind. Four people were crammed in the cab. I tossed my rucksack on the back and climbed on. The truck was old and battered and the springs had long ago collapsed. I stood holding a rail behind the cab and used my legs as shock absorbers to soften the jolts from potholes and rocks as the truck bounced and crashed along the road.

It came to me then, one of those perfect moments when all things hang suspended in crystalline perfection, like the lingering vibration of a struck bell after its sound has faded away. At the far borders of the Oaxaca valley the dun hills came down to the green and fertile valley floor, nopal cactus grew in clumps by the road. A flight of swallows swooped and wheeled. A hawk spiraled upwards and crickets scritched in the stubbled fields. The air was clean and sharp, the sky a vast inverted bowl of purest lapis.

I slipped free of my body and rose up into the sky and looked down at the tiny truck making a dust plume and myself swaying with the truck’s motion and flying along in perfect balance and harmony with all things. My serape streamed in the wind. My hat hung down my back on a braided leather thong, and my blue steel Walther was snugged flat in its thin leather holster against my right hip. All was as it should be.

The beauty of the moment and the freedom from my past combined in one fragile instant and I almost believed it could last forever. It was the last perfect moment before everything went bad, before I saw blood flowing freely over broken stone like a mountain stream in spring.

The old truck flew along the road and I flew with it, surfing all of creation from the back of a rusty pick-up truck and holding fast to the moment, to this life, all I now had of a life once dedicated to a higher purpose.

The truck turned onto another dirt track and stopped to let me off. I waved to the driver and started the two-mile walk towards the Pan American Highway, that long, ambitious ribbon of asphalt connecting air-conditioned America with Mexico and Central America. I intended to catch a bus or hitch a ride into La Ciudad de Oaxaca.

About a half-mile from the highway a coyote loped into the road, stopped, sat on his haunches and stared directly at me. I halted in mid stride and held perfectly still. Coyotes are elusive animals, a long howl in the night, shadows slipping between shadows.

The lean animal cocked his head and grinned at me, a wise knowing grin, his mouth open wide, tongue lolling out to one side. He stalked closer, holding my eyes with an intense stare. Then he turned and walked to the edge of the road, looking over his shoulder at me as if he wanted me to follow him. He spun in a full circle and in two bounds disappeared into the brush.

Indians believe the coyote is a trickster, or a harbinger of disaster, or an agent of warning. Indians have many and varied stories about coyotes, but they all agree that a sighting such as this was ominous. What you believe in a warm well lighted room with ice clinking in your glass while discussing native folkways with a group of friends can be very different from what you believe when you’re alone on an empty road in the center of a valley soaked for centuries in the blood of human sacrifice, and after living for weeks among people whose lives are ruled by belief in the supernatural.

I bent down to examine the coyote’s tracks, real tracks made by a flesh and blood animal, not an apparition. A handful of dust from the road sifting through my fingers sent a tiny frisson of fear through me. I settled my rucksack on my shoulders and walked on.

Near the highway an abandoned shack slumped in the shade of a cottonwood tree. As I neared the tumbledown building I saw a bright red Chevrolet convertible with the top down parked behind it. Anastacio Lagarto was sitting on the hood.

I knew Lagarto as a drug dealer who hung out around the zocolo-the town center of the city of Oaxaca. Lagarto was whip thin, with a narrow face, a backward sloping forehead, a receding chin, and narrow slanted eyes. He gave the impression of a long, skinny lizard anticipating its next fly. A thick gold chain glinted around his neck. He wore what he always wore: a black rancher’s hat, a shiny western shirt with pearl snaps, tight pants and cowboy boots.

One of his hangers on, a stocky Indio in jeans, a straw hat and a cowboy shirt, leaned against the front fender on the far side of the car. The Indian held his right hand low, out of sight behind the fender.

“Buenos Dias, Señor Browning,” Lagarto said. “How you doing this nice day Mr. Roberto?”

Lagarto always spoke in a smarmy, supercilious manner, as if he had a secret that made him superior to everyone else. I stopped in the road and let my rucksack slip to the ground.

“Nice car,” I said.

“I bought it from those kids, got a bill of sale and everything. They needed more money for their mota deal. Lucky I can help them.”

“Too bad about what happened to them.”

“Some scary brujos around here.”

I suspected Lagarto had a hand in the deaths of two surfers from one of the beach towns near Los Angeles who had come to Oaxaca to score some weed. Due to the way kids were killed, and because their bodies were found at a Pre-Columbian site, talk was that they had been killed by a brujo.

“You’re a long way from the zocolo,” I said

“I waiting for you. I thinking you might want to do some business.”

“I’m not in your business Lagarto.”

“What, you don’t like money? You can’t make no money from those blankets.”

“Just blankets. That’s all.”

“You want five thousand dollars? Not pesos, dollars. I give you five thousand dollars for any old stuff you got with you. That’s good, yes?”

“Old stuff?”

“We know you been digging in the old places. I take a chance. Maybe what you got is worth something, maybe not.”

“What makes you think I have anything worth that much money?”

“Maybe you got lucky. Maybe you got some little gold thing I might like.”

Gold thing? That wasn’t a guess. My grandfather told me that if you lie down with dogs you get up with fleas. My grandfather was right about most things.

“I don’t have anything for you.”

Lagarto slid off the hood and faced me. He wore a smirk that said he knew something I didn’t.

“You sure? Nothing you want to sell?”

“You want a nice Zapotec blanket, hand woven, natural dyes?”

Lagarto turned and walked towards the driver’s door, his intention in the set of his shoulders, the lines at the edge of his mouth, his cocky stride. The Indio moved around to the front of the car and stopped by the chrome grille. He had an unsheathed machete in his right hand. Lagarto reached in the car and started to pull out a double- barreled shotgun.

My Walther is in my hand and aimed at Lagarto’s head before he gets the gun out of the car.

“Put it down!”

Lagarto freezes.

“Do it now!”

The Indio shuffles forward.

“Y tu! ” I say to the Indio, watching him with peripheral vision, eyes still on Lagarto.

“Drop the machete!”

The muscles in the Indio’s right forearm flex. His knuckles whiten around the grip. He sets his left foot. He pushes off leaping towards me. I shoot his trailing foot. The small caliber weapon makes a flat SNAP. I see the bullet enter the top of his boot and swing back to Lagarto before he can react, my sightline on his left eye.

The Indian drops the machete, falls and curls onto his side holding his foot, grunting, “Uh, uh, uh.”

“Put down the gun Lagarto!”

Lagarto hesitates. I consider shooting his left earlobe off to encourage him. He doesn’t need that earlobe, blood spraying, yelling. Beautiful. Probably teach him some humility. I resist the temptation.

“Is today the day?” I ask.

“What you mean? What day?”

“The day you’ve chosen to die.”

Lagarto lets the shotgun slide onto the car seat.

“Move away from the car.”

Lagarto moves slowly, his eyes shiny marbles, nothing behind them. He tries a smile, a reptile peeling back its thin lips. He licks his lips. For a second his tongue looks forked.

“Man, why you shoot Manuel? We were…”

“On your knees,” I say.

“Come on man, my pants get dirty.”

“This can be the day.”

“OK, OK,” going to his knees in the dirt.

“Hands on your head, move towards me.”

His shiny black pants scuff on the rough ground. The Indian stays curled on his side holding his foot and whimpering. I don’t see or feel anyone else in the area. I step behind Lagarto and run my left hand over him, checking his waistband, patting his pockets. I find a seven-inch Tijuana switchblade in his boot and slip it behind my belt.

“You use this on those kids?”

“I don’t hurt nobody.”

I leave Lagarto kneeling in the dirt, go to the Indian and quickly search him. No weapons. I tell him to take his boot off. The hollow point bullet made a small entry hole at the top of his arch and ripped a half-dollar sized exit hole underneath. A small crimson pool forms in the dust and soaks into the dry and thirsty earth. I toss a handkerchief in his face.

“Put some pressure on that wound.”

The keys are in the ignition. The shotgun is an old Stevens sixteen gauge, the blue worn away and a coat of rust on the receiver.

“Help your buddy,” I say to Lagarto. “Bring him to the car.”

I lay the shotgun on the ground away from the car, grab the keys with my left hand and pop the trunk. Lagarto comes to the car with Manuel leaning on his shoulder. I move back, my handgun still on Lagarto.

“Get in the trunk.”

Lagarto’s face goes pale. “What you doing man? You acting like a crazy guy.”

“You offered me a ride to town. I’m driving and you’re riding where I don’t have to watch you.”

He licks his lips, that forked tongue again, my imagination running away with me.

“What’s the matter Lagarto? Macho guy like you, not afraid of small spaces are you?”

“You really taking…?”

“I wanted you dead I wouldn’t have to take you anywhere. Right? I’m the guy with the gun. You’re the guy with empty hands.”

After some mumbled cursing Lagarto climbs into the trunk. The Indian follows him.

“Keep pressure on that foot. Use your shirt if the handkerchief doesn’t stop the bleeding.”

I closed the lid on them. Using the slide mounted safety I dropped the hammer on my automatic and holstered it, then broke open the shotgun and removed the shells. Buckshot. I pocketed the shells and leaned the old double barrel and the machete against a tree for a campesino to find and put to better use. The cheap switchblade went in a ditch with dirt scuffed over it. I tossed my hat and serape on the floor of the car settled into the soft seat and started the engine. The softly sprung convertible bumped down the dirt road to the pavement. I headed north towards La Ciudad de Oaxaca.

Chapter Three

It had been self indulgent to shoot the Indio in the foot. He could have gotten to me and split my head open with his machete in less than two seconds. But I didn’t want to take another man’s life. Besides, two seconds is a very long time and the shot was nothing. If a hit to the foot didn’t drop him, I would have had plenty of time for the headshot, for two headshots.

Still, Dillon’s words after my first mission came back to me. He had been my team leader and used my code name to let me know he was serious, “Priest, you can’t shoot a man a little bit. You have to put them down. You’re the finest natural shot I’ve ever known. But lad, your soft heart and over confidence will get you killed one day.”

Maybe so. Maybe one day. But not today.

Now I had problems. I had been living quietly and keeping a low profile. Now Lagarto knew I carried a gun and was willing to use it, not the usual behavior of a blanket trader, or a dealer in antiquities. He would talk. Word would get around. Suspicions would be raised. The situation with Lagarto added to the shifting atmosphere I had felt around Oaxaca lately. The deaths of the L.A. surfers had seemed to trigger a sea change. An undefined looming presence was gathering, like charged air before a tropical storm.

Had a brujo killed those kids? I couldn’t see a connection between an Indian sorcerer and a couple of surfers on a weed buying expedition. Brujos were concerned with darker matters than hustling a few pounds of weed. It seemed more likely that a drug dealer had killed the surfers, Lagarto being the primary possibility. I had seen him talking to the fresh-faced kids parked in the zocolo in their new Chevy convertible when they first came to Oaxaca.

That same day I had seen one of Lagarto’s customers, stoned out of her mind on God only knows what, walking along the yellow stripe in the center of the street around the zocolo, carefully putting one foot in front of the other as if balanced on a high wire, her only clothing a pair of red lacy bikini panties. One of the ladies who sold rebozos on the zocolo covered her with a large shawl and led her away, docile as a kitten.

Half of my generation was smoking weed or hash, dropping acid, eating mushrooms and cactus buds, trying to break on through to the other side, or just get stoned. The other half were trying to figure out what was going down. But acid soaked sugar cubes weren’t getting anyone to the place they thought they were looking for. Mick Jagger wasn’t getting any satisfaction and neither was anyone else.

Early in the year someone had hit a button marked CRAZY and was holding it down. John Lennon was singing about a bloodless revolution and the Russians were rolling tanks in Prague, steel treads chewing up ancient cobblestones and the people who ran before them. In Paris, students barricaded the streets and fought pitched battles with police. The crash and rattle of gunfire continued in a small Asian country where some of my former comrades were reported to have destroyed a village in order to save it.

In Alabama blood ran red on brown skin and crosses burned in churchyards at night. On a spring day that year, in a leafy Southern city, we killed a King, sending cities into flames and bodies hitting the sidewalks from sea to shining sea. And on a summer night in a city without a soul we murdered a prince, sending most of a generation into despair and me into exile. How many degrees of separation are required for your hands to be free of stain? I think for some sins no degree of separation is enough for us to be blameless. Are we not all our brother’s keepers?

The backbeat was hard and heavy, the drums were beating faster and the world was spinning out of control. Here, where the old ways still ruled, where life was lived closer to the bone, where the colors were richer and the air like wine, I thought I had found a way to get off. But the world was catching up to me.

It was easy to drift south on the Pan Am Highway. A few more American kids looking for drugged out bliss had arrived in Oaxaca during the past month. None of them I had met understood that they had left their comfortable world and had traveled back in time to a culture that was essentially medieval. The ones I had talked with seemed to think they were in some kind of Mexicoland, constructed by Disney for their enjoyment. They skated easily along smiling at the happy brown people not knowing how thin the ice was under them or what horrors lay beneath.

How could Lagarto have known I would be on that road at that time? How did he know I had found a gold piece? No one knew my schedule except Raphael. Could Lagarto have bribed one of the men on my excavation crew? I knew how to get the answers. I had attended the interrogation classes and had seen it done. But I didn’t have the heart for it, then or now. Torture is a filthy business regardless of what you call it.

Nor was I sure how much I should care about any of it. The surfers were someone else’s problem. I could deal with the problems Lagarto represented as I had dealt with the problem in Los Angeles. I could run. I didn’t want to get involved in local intrigue, or come to the attention of my former organization.

But where would I go? I didn’t have any paper that would allow me to get on an international flight without popping up on the U.S. government’s radar. The only passport I carried was in my true name, Jesse J. Rideout, an easy name to remember, a name that was in U.S. government computers, and one that cost me many skinned and bloody knuckles as a kid. I had been named by my grandfather, who was born in 1863, lived to be 97, and failed to understand why my name was cause for fights at each new school.

I had two blank tourist cards. But Mexican tourist cards were no good outside of Mexico. I could easily slip across the border to the north or to the south. But returning to the U.S. was not an option and I couldn’t go to Guatemala without running the risk of recognition by former teammates.

Well, I could worry about all that later. Mexico was a big country. Robert Browning could disappear from Oaxaca as easily as he had appeared at the border. For a man on the run to use a poet’s name seemed whimsical. But I had been reading Browning while staging in L.A. and it was the first name that popped into mind when the Mexican immigration officer who sold me the tourist cards asked me what name I wanted typed on the first one. The name hadn’t drawn attention and I supposed William Blake, or George Byron, could easily appear in the Yucatán or on the Gulf Coast. Vera Cruz might be a good town.

Something was giving me that prickling, icy feeling between the shoulder blades you get when someone is watching you. The coyote, the vision, or whatever it was I had seen when I took the gold medallion from its resting place, the hollow people, all were part of the heavy foreboding atmosphere. Maybe I should move on.

I stopped on a quiet street lined with the stone walls of inward turned houses, opened the trunk and stood back to let Lagarto and Manuel crawl out blinking into the late afternoon sunlight.

“Manuel,” I said.

Manuel leaned on the side of the car favoring his wounded foot. The handkerchief was soaked through but the bleeding seemed to have stopped.

“Get some penicillin and iodine at the farmacia. Clean that wound and bandage it. If you have to go to a medico tell him you shot yourself while cleaning your gun. Entiendes-you understand?”

“The fuck you care man?” Lagarto asked. “You the one shot him. Now you a fucking nurse or something?”

I ignored Lagarto and his vulgarity.

“Manuel, you understand? Take care of yourself and don’t come at me again. Next time I won’t shoot your foot. Talk to me Manuel. Tell me you understand.”

Manuel nodded, “Sí, claro.”

I tossed the keys to Lagarto and he slid behind the wheel.

“Lagarto, I don’t want to hear any more about this. Forget about doing business with me. Forget this afternoon.”

Lagarto slouched behind the wheel of the Chevy, big car, tough guy. “You shoot my friend. Fuck I’m supposed to do? Forget about it?”

“Manuel is going to forget about it. Right Manuel?”

The Indian nodded his head.

Largarto stared at me without blinking. I could almost see scales forming on his flat cheeks, growing forward from his ears and covering his face. “You sticking your nose in places it don’t belong, hanging out in villages, talking to Indians. Maybe you heard of Sangre de Dios.”

Blood of God? What was he talking about, some church thing?

“You taking communion? You an altar boy?”

“Don’t laugh gringo. You don’t do business with me, somebody else gonna have some business with you. Your pistola won’t help with him. Better for you, sell me that little gold thing. I give you another thousand, six thousand dollars.”

“It’s not happening.”

“You don’t know about Sangre de Dios too bad for you.”

“Adios Lagarto.”

I stepped away and slapped the side of the car and watched them drive off in the long convertible, a car made for fun, for cruising the beach and picking up girls on summer nights, a car that had carried its previous owner to an early death. I didn’t think this bright red Chevy would bring much fun to its new owner.

Chapter Four

I stuffed my serape under the flap of my rucksack, slung it over one shoulder and headed for my hotel. Oaxaca is a town of thick stone walled buildings, hidden courtyards, and soft voiced polite people. It is also the center of the Zapotec world. The Zapotec have been craftsmen and traders for all of recorded history. As a people they are cheerful, charming, and intense, quick to make friends and quick to violence. Zapata, the Indian revolutionary came from Oaxaca, as did Benito Juarez, one time president of the Mexican Republic.

After a few weeks in Mexico City, and after Elizabeth disappeared, I had gone to the road again. While stopping for a day in Oaxaca I had been beguiled by the life of the zocolo, the rococo bandstand where a brass band played on Sundays and families gathered to listen, the parents in their Sunday best, the little girls in starched white dresses, the boys in white shirts with wet hair combed straight back. Always there were vendors selling serapes, rebozos, iced jugo de naranja, candy, ice cream, lottery tickets, brightly colored balloons, and chewing gum. In the evenings musicians strolled and fingered guitar strings. The teenaged boys walked one way and the girls another, around and around the central bandstand, casting looks of youthful yearning at one another.

As I crossed the zocolo Alma called to me, “Señor Roberto!” She ran towards me, her black hair streaming behind her, one hand holding the little box she always carried the other swinging free. I dropped my rucksack on a green painted iron bench.

Alma skidded to a stop, all in a rush and breathless. She wore one of her thin print dresses white anklets and black shoes with a strap across the instep. The silver cross earrings she always wore caught the sunlight. Alma was eight years old, one of the kids who sold Chiclets in the zocolo

Kids her age probably sold raw chicle, the original chewing gum made from the sap of the chicle tree, a thousand years ago. Now the chicle had been packaged and marketed by an American company. They even trademarked the name of the tree. The only thing that had changed was that the profits flowed back to a corporation rather than staying in the pockets of local people.

“Where have you been this time Señor Roberto?”

“The mountains niña.”

“What is in the mountains?”

“Sit here on the bench and I will tell you.”

“Oh, I almost forgot. The lady said it was muy importante.”

She reached in her pocket, brought out a white rose and held it out to me, “The lady said to give this to you.”

Alma said a woman from a nearby village had come to the zocolo and given her this flower and told to her to give it to me when she saw me this afternoon. She didn’t know the woman’s name or how she knew Alma would be seeing me.

“Why did she send a white rose?”

“She said you would know. She wants you to come to her village right away to meet her tía.”

To meet her aunt? It was probably someone who heard I was buying artifacts. “I’ll see her later.”

“What about the mountains?”

“I went to see the great dance of the osos- the bears. At this time of year all the gentlemen bears come down from the mountaintops to the meadows to be with the lady bears.”

“It is true?”

“Sí, of course, completely true.”

Three of Lagarto’s people were staring at me from their spot on the far side of the zocolo. Usually we ignored each other.

“The mountain meadows are covered with flowers of all colors and kinds. Like all ladies, the lady bears love flowers. But in the case of bears they eat the flowers.”

Alma giggled, and squirmed around on the bench.

“The ladies are very nimble with their claws, as you are with your little fingers. They carefully pluck each flower and delicately nibble the petals.”

“But what about the men? Do they eat flowers?”

“Certainly not. The men are a rougher sort of creature than the ladies.”

One of Lagarto’s men was giving me a mad dog stare, a thick-bodied Indian with a bad attitude and a face like an exploding grenade. I ignored him.

“So they are like people,” shrugging. “But what do the men eat?”

“Peanuts mostly. Groves of peanut trees as tall as the steeple on the church grow on the mountaintops. The male bears gobble peanuts with much snuffling and drooling. They only behave as gentlemen when there are ladies present.”

“Again much like people,” Alma said, tossing her hair and turning the corners of her mouth down.

“I’m afraid so.” “And next?”

“The gentlemen bears stop at clear mountain streams to wash their faces before meeting the ladies.”

“Yes, I can see this, like gentlemen before they take a lady to dinner.”

His name was Chico, the one dogging me. He was starting to get on my nerves. “Then they dance. They rise up on their back legs and form a ring around the

meadow, so that there is one gentleman and then one lady all around the circle, which may have, oh, forty or fifty bears in it. They take two steps in one direction and one step in the other, circling the meadow and sliding by one another and changing partners. They dance under moonlight swaying from side to side and talking in their low rumbly

voices. After the dancing they decide who will marry with whom. In this way each gentleman and each lady will find the right partner.”

Chico started across the zocolo towards me. Ignoring them never works. Alma was looking up at me but she was seeing the meadows and the bears and the moonlight.

“ Ah,” she said. “Like the young men and women who walk around the zocolo.” “Just like that.”

“Señor Roberto, tell me, do you think any of the lady bears might come to the mercado to eat the flowers there?”

“Well… Uh, I don’t think…”

“Roberto,” Alma said with a chiding tone, putting one hand on her hip, or where her hip would be if she had one. For a moment she looked like all women exasperated with the dullness of men. “I mean pretend bears, not real bears.”

I had forgotten for a moment our conspiracy of make believe.

“Oh. Well. Of course, pretend bears might well come to the mercado to eat flowers.”

An ice cream vendor pushing a white cart came jingling by our bench calling, “Helados.”

Chico was closing fast on our bench, his boot heels slamming on the pavement.

I stood and faced him, letting him see my eyes and what he was about to get into, “Hey

Chuy, want an ice cream?”

Chico stopped so quickly he stumbled and almost fell. Until now I had maintained an image of the friendly, inoffensive gringo, selling Indian blankets so I could hang out in Mexico. Now I let some of the other me show, the one known as Priest. Chico stared at me and reevaluated the situation. He looked over his shoulder at his friends, too far away to help.

“My name is Chico,” he said, his chin and chest pushed out. His posture said he was ready to fight, but his eyes said his body was lying.

“How about strawberry Chuy. Esta muy sabroso.”

“Later I see you gringo,” Chico said, and spinning on one boot heel, headed back to his boys.

Alma ate her ice cream, licking the edges and catching the drips as they ran down the side of the cone. In the fading sunlight with the softer rhythms of early evening emerging she told me about events in her world of the zocolo: which vendors were most successful, what the Americanos had been doing, who was new in town.

She thanked me with solemn courtesy for the ice cream and I gave her ten pesos for her box of Chiclets, the standard price we had previously agreed upon.

“You know you pay too much.”

“It’s for the convenience. This way I get a whole box at one time.”

“Why do you buy so many cheeklits?”

“Xavier would be devastated if I did not bring them for him. “Xavier?”

“My parrot. He loves chewing gum.”

“Is he a real parrot or a pretend parrot?”

“Certainly he is a real parrot, one who likes chewing gum beyond all other things.”

Alma looked down at the sidewalk and thought for a moment. Then she looked up at me and said, “Roberto, please remember that I am eight years old. I will soon be grown.”

We said our goodbyes and I tucked the box of gum and the white rose into my rucksack. Alma skipped along the walkway and disappeared into the crowd around the zocolo. In America she would have been ashamed because she was poor. Being poor in Mexico was simply a state of being, not a sin. Here she had her place and was making her way, known and cared for by many.

Lagarto’s zocolo cowboys were gone.

Chapter Five

I walked the few blocks to my hotel.

“Hola, I said to Reyes, one of the hotel’s three security guards, a thick chested man wearing a white shirt and a jacket covering the .38 revolver he carried in a well- worn hip holster. Alberto, the hotel manager, a smiling amiable man, came from behind the counter and handed me a stack of mail and the key to my room. Alberto wore a dark suit and white shirt with a thin tie. He had receding hair, a narrow mustache, and the air of a man with too much on his mind.

“How was your journey Sr. Browning?” “Robert, please call me Robert.”

“Bueno pues, Robert.”

The hotel was built around an open three-story atrium and was cool inside, even on the hottest days. I climbed the stairs to my rooftop room. From my windows I could see over the red and orange tiled roofs of the city. I paid rent a month in advance and got a fair price, good service and security. Only guests and employees got by the front desk and only maids came to my aerie. I tipped appropriately, not too much, which would

be the act of an arrogant gringo, and not too little, which would show disrespect. My laundry was done promptly, nothing was ever missing from my room and it was always

clean.

A wool blanket woven in patterns taken from the walls of the excavated ball court at Mitla covered my bed, dyed with extracts from flowers, tree bark, onionskin, and cochineal. I dropped my rucksack on the bed, my stack of unread mail in a square basket, and the Chiclets in a large pot overflowing with packages of chewing gum. The white rose went into a Zapotec pot at least three hundred years old. I sat on the bed and

pulled off my dusty boots.

In one corner were a few dozen hand woven Zapotec serapes, the highest expression of the craft. Using the Robert Browning name I had sent photos of the weavings to galleries in Paris, Los Angeles, and New York where they sold as wall hangings. The income provided a living for three Zapotec weaving families and paid for most of my expenses. The serapes had also, until today, served as my public reason for being in Oaxaca.

A heavy stone Chac Mul, the rain god, squatted next to a window. Stacks of books and dozens of low grade Pre-Columbian artifacts covered bookshelves and tabletops: fragments of pots, carvings in stone and jade, obsidian projectile points, the detritus of civilizations blown away, chaff before the whirlwind of the Spanish conquest.

The large rectangular room occupied about a third of the hotel roof, the rest served as my terrace. Brilliant crimson bougainvillea cascaded over the white walls outside my windows. By day I floated in a flower-covered sanctuary above the city. At night I sat outside, drifting in a pool of darkness over the city lights.

I showered, and shaved two weeks of beard, studying the face that emerged. Deep tan, sun bleached hair cut shorter than the current fashion, intense eyes, a too serious face, the face of a young man who thinks too much, perhaps the face of a failed priest, or a revolutionary, or a man on the run.

I changed into tan tropical worsted slacks and a fresh blue broadcloth shirt. Item by item I emptied my rucksack, dumping my field gear on the floor and placing the artifacts on the desk. Wrapped in sisal were a dozen or so small jade caritas, carvings

of god faces. A burlap bag the size of a loaf of bread bulged with jade beads, at least a couple of hundred, all drilled by hand powered pump drills that had been in common use in Pre-Columbian America.

Carefully wrapped in a scrap of serape wool was a polychrome pot with a thin crack running down the side. It was about five inches tall and painted in faded tones of

ocher, black, and earth. It would bring a few thousand from a museum director in one of

the mid-western states who was building his Pre-Columbian collection and was hungry for almost anything. The caritas sold for a thousand each to a gallery Paris. The jade beads brought a hundred each. All in all a good find. Emiliano now had money to buy new looms and more wool to expand his family’s weaving business. Once I converted these items to cash I would have enough to buy months of freedom, maybe a year.

I unwrapped the gold medallion from the threadbare denim shirt. It was heavy, soft and buttery yellow. The piece was identical to a gold medallion Raphael and I had found in Yucatán two months ago, the piece that ignited a fire in both of us to find the secrets of the ancient cultures all but destroyed by the Spanish. Only fragments of those cultures remained, still living in forgotten corners of the countryside and the hearts of reclusive Indians.

The gold piece measured about four inches top to bottom, three inches wide, and a half inch thick. There was a hole at each corner near the top, obviously for cords so it could be worn on the chest. It was engraved with a pyramid overlaying a circle with four small circles connected to the center circle around the edge. Inside each circle was a

tiny glyph. A small triangular opening went through the very center of the circle and the pyramid. Under my magnifying glass the glyphs looked like the faces of fearsome deities.

The medallion seemed to glow with an inner radiance. Day by day the supernatural beliefs of the Indians seemed more real. Possibly this piece contained some kind of power. I remembered the flicker of a vision that had come to me when I first touched the gold piece in its resting place of centuries. A golden skinned man wielding

an obsidian dagger, the screams of multitudes. Feathers swaying as he bent over his victim. Imagination? Maybe. Maybe not.

On a rational level I thought my perceptions were fanciful, that my overheated imagination produced the radiance. But I also knew that I could sometimes see things that others could not.

Finding two such artifacts was, as far as I knew, unprecedented. Professor

Mendoza, the director of the National Museo de Antropología, would be thrilled to place this one in the museum with its twin. I was looking forward to showing the piece to Raphael tonight.

I had met Raphael at a sidewalk cafe in Paris. It was a leafy spring day and I sat with two students and a professor I had met at the cafe. They were berating me, in French, for my government’s policies and the war in Vietnam. My grasp of French was tenuous but the meaning was coming through.

At the next table a slim, well-dressed man with ink black hair and a falcon’s nose had been listening to the uneven interchange. He leaned over and spoke in English to my café companions.

“Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Raphael Lorenzo Mendoza de Alvarez. I could not help overhearing your conversation. I feel compelled to make a comment.” With a friendly smile, and in the same polite, cultured manner he said, “The three of you should go fuck yourselves.”

Raphael turned to me, “These pissants understand English quite well. They’re just messing with you.” He turned to them again. They were open mouthed, frozen.

“So what if America is fighting in your former colony? They were left with the mess France created with its colonial policies and slave labor plantations. France didn’t have any scruples about armed force in Vietnam until you got your asses kicked at Dien Bein Phu. Talk your merde to me. I understand you very well.”

The café intellectuals had no stomach for harsh words. They fled in disorder with much scraping of chairs and muttered comments and leaving me with their bill.

Raphael was the youngest son of a wealthy Mexican family. He had been educated at the Sorbonne, and U.C.L.A. He operated a business in Mexico and traveled to parties, carnivals, and festivals on three continents because, he said, “I want to experience the happiness and joy of life.”

He seemed to know everyone. One evening, while strolling on the Isle de Cite, we stopped next to a small woman with short frizzy hair sitting on the bank of the Seine. She wore a simple black dress and kicked her bare feet in the water while singing “Mon Legionnaire” with great tenderness to a toy soldier she held in her lap. Raphael sat on the grass next to her and I went a little way down the riverbank to give them the privacy the moment seemed to want. They talked quietly for a few minutes then he rejoined me. I asked him what they talked about.

”Oh, Edith is a nice lady. She’s just a little crazy, nothing she can help. Like many of us she would like to be someone she’s not.”

Raphael had called a few days before my departure for the hills and asked me

to meet him at his uncle Francisco’s estate when I returned. He had found something, “extraordinary.” He wouldn’t tell me more, except that it was, “of the deepest interest.”

Chapter Six

Time to go. I placed the caritas, the jade beads, and the pot into a small bag and opened a window onto the ventilation shaft. I leaned out of the window and slid the bag into a cubbyhole above the window. When I found the niche I put two hundred pesos in it and left the money there while I was away for a few days. The money was undisturbed when I returned. I now used it as a secure hiding place. I didn’t worry about the artifacts scattered around my room. They were either too large to easily carry, or they were of relatively low value. So far the hotel staff had been trustworthy but there was no need to put temptation in their way.

I ran a cleaning patch through the bore of my handgun, replaced the round I had fired, and slipped the automatic in its thin horsehide scabbard in my rear pocket where it wouldn’t be seen if I removed my jacket. I dropped a spare magazine with ten rounds into the left front pocket of my pants. My horn handled French folding knife with the corkscrew went in my right front pants pocket in case I encountered a bottle of wine in the course of the evening. I pulled on a lightweight suede jacket and put a wad of small money in my jacket pocket. In town I budgeted fifty pesos a day to hand out to beggars, people so undone by life that they couldn’t even get it together to sell chewing gum on

the street. Many of them were Indians, alcoholics wasted on cheap pulque. Who was I to judge?

As I reached for my pocket compass I noticed that the needle was pointing at the gold medallion. I stepped away from the desk with the compass and watched the needle spin until it was pointed to north. When I put the compass back on the desk the needle spun again and pointed at the medallion.Compass needles can be deflected from their northern orientation if they are close to something made of ferrous metal, such as a firearm, a knife, or a car. Gold is not

ferrous. I removed the compass from the desk and put it back a few times. The result was the same each time. Maybe there was some iron ore mixed in with the gold.

I slipped the medallion inside a clean sock and put it in my canvas shoulder bag next to my Nikon, a copy of B. Traven’s “The White Rose,” and “The Conquest of New Spain,” by Bernal Diaz del Castillo, and a few other items. I slung the bag over my shoulder and locked the door on my way out.

Reyes unlocked the garage inside the hotel compound where the Mustang lived when I was in the hills. He swung open the double doors to the street. I stashed my bag behind the passenger seat. With the engine’s rumble echoing from the courtyard walls I waved thanks and drove across the courtyard and into the cobbled street.

Oaxaca in late evening is muted lights, deepening shadows, and soft sunset colors. I drove slowly through the city and past the small houses on the outskirts of town painted turquoise, yellow, aqua, and a dozen shaded colors, all transformed by the fading sunset into a fantastic candy colored children’s playground.

I drove with the windows down and the heady scent of night blooming jasmine on the evening breeze. Francisco Alvarez’s estate was on a road that ran near Monte Alban, an ancient city at the top of the tallest mountain on the valley floor. At the center of Monte Alban was an enormous pyramid that loomed over the valley like a dark shadow. On that pyramid, like dozens of others in Mexico, the smoke of sacrificial fires had risen into the clean air for a thousand years. On a hot day I thought I could smell the scent of blood coming out of the stones, and sometimes I heard screams of terror echoing down the centuries. Tonight the night wind seemed to carry the cries of the L.A. surfers who had died on that blood drenched altar stone, sacrificed to a brutal unknown god, or perhaps to the modern deity: greed.

The countryside was open and stretched away into the fading light. I slowed at the turn to Francisco’s. One of the hollow people leaned against a tree on the side of the road. I thought of them as hollow because they seem to lack substance, as if they were some kind of simulacrums.

I first encountered them one night when I had stopped on the road to Tehuacan to give a ride to a family standing and waving at the side of the road. The man sat in front with me, the woman and boy crammed themselves into the Mustang’s tiny back seat. Their clothing was dusty and the man’s face was covered with sweat, but they had no smell whatever.

They sat silently as I drove through the night. I concentrated on the winding road in my headlights. I was not tired, but I dozed and then snapped awake. I looked to my right and for a moment the man had the face of a weasel. The weasel turned towards me, its eyes red rimmed and burning, its fangs dripping. Then the illusion, or vision, faded like an old photo and he was just a tired Mexican campesino. I stopped to let them off at a dirt road that wound into the hills.

“Por favor, give me something,” he said. “What do you need, money?”

“Anything.”

I gave him some pesos, a roasted chicken and a stack of tortillas I had bought at my last stop. Neither the woman nor the boy spoke. As I pulled into the road I looked in the mirror. No one was there. The moonlight was bright. There were no shadows, no place for them to have gone. Suddenly the back of my neck went to ice. I was walking point and someone had me in his sights.

Since that night I had seen one or more of them from time to time, usually along an empty road or at the edge of a village. They disappeared as abruptly as they appeared. As I made the turn onto the road to the Alvarez property I twisted around and looked out my rear window. The hollow man had disappeared.

The usual high wall surrounded Francisco’s hacienda. The gate was open to a long sweeping driveway leading up to a classic Spanish home, with red tile roof, white walls and a wide veranda under a deep overhang, draperies of bougainvillea hung from the roof. As I passed through the open gate Virgil, the houseman, waved at me with his right hand. His left arm cradled a double-barreled twelve-gauge shotgun. I parked in the driveway walked to the door and knocked.

You cand find The Jaguar’s Heart on Amazon

http://www.amazon.com/Jaguars-Heart-James-Morgan-Ayres-ebook/dp/B001TK411Y

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End