We recently met a family of Yurok Nomads in Turkey, part of an extended clan. Their immediate family was composed of: grandmother, who was over 100; mother and father; son and daughter-in-law, and a six year old granddaughter. Our visit was arranged by friends, Ayse and Johnny. Ayse acted as interpreter.

This family’s livelihood comes from their herd of 250 goats, cherries they pick from trees surrounding their summer pasture high in The Taurus Mountains, and almonds that grow at their lower elevation encampment in a valley overlooking the Mediterranean where they spend the winter. Villagers and city people alike come to their encampment to buy goat cheese and other produce. In spring they sell some of their herd, including some of the new lambs. They maintain their herd at a carefully considered, balanced, and constant size. More than 250 goats would overgraze the available land. Fewer would not provide an adequate living.

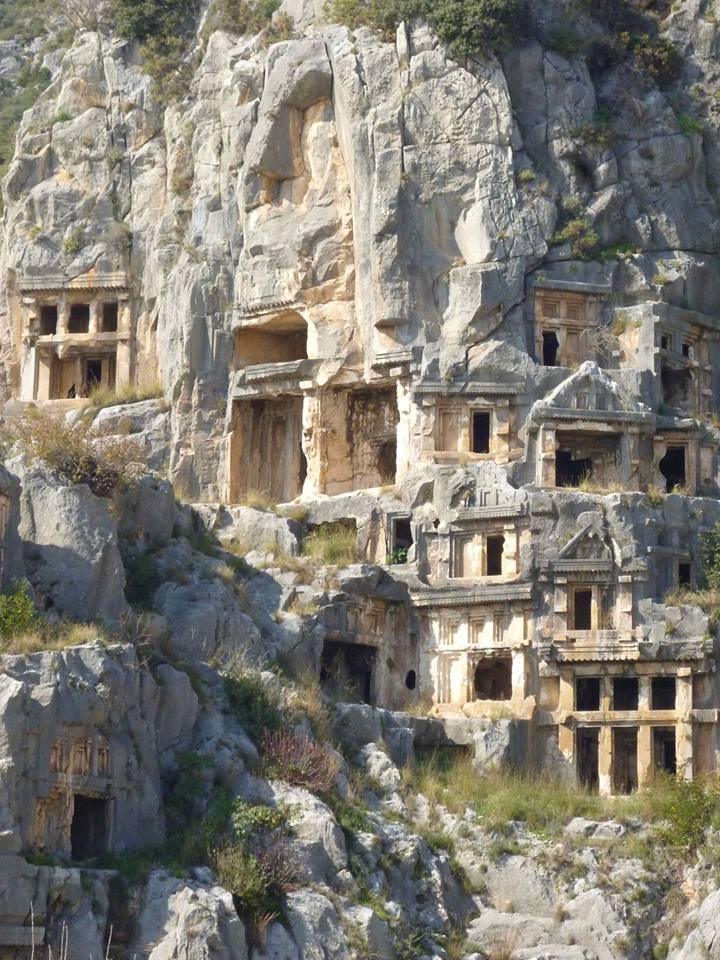

The Yuroks way of life is protected by the Turkish government, which has set aside millions of acres for the nomad clans to live as they have for centuries. Each spring they break down their tents, pack their possessions, and herding their goats ahead of them trek to high meadows. In autumn they return to the lower encampment. The Yuroks’ way of life is older than the ancient stone cities that lie in ruins along their migration path. They have, however, adapted to today’s world and make use of some of its conveniences. Instead of the traditional tents of canvas and wool, and before that of animal skins, they cover the frame work of their tents with plastic sheeting, which is waterproof, translucent, and easier to maintain. The framework is, as traditional, built from dried and worked saplings lashed together. In winter, insulation is provided by flattened cardboard boxes inside the outer plastic skin, secured to the wooden framework, an inexpensive and practical adaptation.

To enter a Yurok dwelling, you first cross a threshold and step into an antechamber that provides a barrier to wind, rain and dust or mud. Here you remove your shoes. Then puling aside a heavy drapery and opening a door you step onto patterned carpets, some hand woven. The carpets are protected from the ground by tarps laid under them.

We visited this family in February during a cold and windy rainstorm. Inside it was warm and cozy; the heat coming from a soba – a wood-burning stove – near the center of the main room. A wall of hanging drapes over a wooden framework separated the main room from private quarters. Around two walls of the main room were low, cushioned divans covered with carpets, patterned spreads and pillows. In the kitchen area a counter at waist height ran along the wall behind the soba. On it was a tall stack of inlaid and carved wooden boxes, a propane stove – and a television.

We visited this family in February during a cold and windy rainstorm. Inside it was warm and cozy; the heat coming from a soba – a wood-burning stove – near the center of the main room. A wall of hanging drapes over a wooden framework separated the main room from private quarters. Around two walls of the main room were low, cushioned divans covered with carpets, patterned spreads and pillows. In the kitchen area a counter at waist height ran along the wall behind the soba. On it was a tall stack of inlaid and carved wooden boxes, a propane stove – and a television.Power lines run along the nearby road, cellular service is available, as is national medical and dental care. The children go to village schools. Although camels still carry much of the clan’s goods during the migration, this family owns a van. They use the van for transporting the heavy items, but the goats walk, and so do those who herd them. When migrating they walk about fifteen miles a day. Even in their encampments the goats must be spread out to graze and brought in at night. Grandmother walks about seven miles a day with the goats.

The Yuroks’ ownership of a motor vehicles appears to be an experiment. Whether the van will be a successful addition or not depends on the rising price of insurance, repairs and most of all fuel. Also, vans, unlike camels, do not reproduce. Nor do they forage for themselves. The Yurok way of life is durable, proven by centuries, and could survive quite well if all the gas in the world dried up, power failed and the banks closed. We, I suspect, would do less well.

Previously our livelihood came from designing original products and international trade. For some years we made two round the world trips each year: from Los Angeles to Hong Kong, then Delhi, Tehran, Frankfort, Milan, New York and back to Los Angeles. We traveled with piles of luggage containing working materials: sketch pads, patterns, sample garments and so on. And with children, who required their own luggage, a stroller, bottles and diapers. Often friends and employees traveled with us. When we appeared at the luggage carousel it looked like the circus, or a rock band, had come to town. A procession of taxis or limos transported us to hotels where we lived much of each year. Our lives would have changed considerably if the 747s had stopped flying, or cars had run out of gas. Camels just wouldn’t have done the job for us at that time.

These days, our livelihood comes from writing and photography, for which we need minimal tools: two MacBook Airs, a Canon G9 digital camera, cell phones for each country, and related cables and chargers – and WiFi connections to the Internet. Our transportation for the past two years has been by foot and train, bus, dolmus, rides from friends and the occasional flight. In Europe that’s worked out well so far; public transportation is available virtually everywhere at reasonable cost, and we’ve avoided the hassles and expense of auto ownership. I bought my first car at fifteen with money I saved, and have had at least one car, often two or three, and motorcycles, trucks and motorhomes, for a half century. It was difficult to imagine being without a car. Now I am motorless and enjoyng the freedom. To a certain extent I miss having a car, but I don’t miss the hassles. Being without a vehicle is a continuing experiment, a mirror image of the Yurok’s experiment. If the Internet went down we’d need to fall back on other skills. And if gas ran out we’d be looking to those camels.

Disclosure: we are NOT paid by any of the companies whose products we review.

GoLite Peak Backpack

Traveling as we do it only makes sense to use backpacks. Previously we had stacks of suitcases, piles of duffle bags and assorted luggage. We also had people to help carry them. We have no such help now, and are adverse to carrying anymore than we must. Minimalism and laziness sometimes amounts to the same thing.

For the past couple of years I’ve been using a backpack made by GoLite, a small company specializing in the manufacture of lightweight outdoor gear: backpacks, sleeping bags, tents and clothing. Some of their products adapt well for travel – my backpack has.

It contains 36 liters, ten more than ML’s little Patagonia Pack. Note please that I used the word, ‘contain,’ not carry. In manufactures’ literature you will often read that this of that pack or bag will ‘carry’ a certain size of a load. Be clear – no bag carries anything. You do. Or, in this case, I do. That being so, no longer will I carry an expedition pack, as I once did. Nor will I tote an overstuffed suitcase or duffle up and down hills or along cobblestoned streets. Wheelies are wretched things if you venture far from smooth pavement and a topic for another post. So, we carry lightweight backpacks containing as little as possible.

It contains 36 liters, ten more than ML’s little Patagonia Pack. Note please that I used the word, ‘contain,’ not carry. In manufactures’ literature you will often read that this of that pack or bag will ‘carry’ a certain size of a load. Be clear – no bag carries anything. You do. Or, in this case, I do. That being so, no longer will I carry an expedition pack, as I once did. Nor will I tote an overstuffed suitcase or duffle up and down hills or along cobblestoned streets. Wheelies are wretched things if you venture far from smooth pavement and a topic for another post. So, we carry lightweight backpacks containing as little as possible.

My personal possessions have never filled this GoLite pack to more than 2/3 capacity. I suspect its capacity is actually greater than its rated 36 liters. I have, however, had this pack stuffed to the top with water and wine bottles, blocks of goat cheese, pails of olives and bags of garden produce. One day at the bazaar I weighed the fully loaded pack on a venders scale. It weighed 21 kilos, a little over 46 pounds and well over its suggested load limit of 20 pounds. Well over mine too. The thing is, the pack was comfortable even with this load. This was due to its design, which keeps the load close to the body, and to its fit.

Most packs come in one size, which contrary to claims to fit all, actually fit few – only those of average size, which I am not. GoLite packs come in sizes, like clothing, like all packs should, and this makes all the difference. The Peak also has a clever system of hooks and loops that can be let out or taken in so that this largish pack can be used as an unobtrusive daypack.  There two small side pockets and one large back pocket. The fabric is sturdy and shows little sign of use, except on a strap where a would-be thief cut it. Lacking an awl, I had it repaired by a local cobbler.

There two small side pockets and one large back pocket. The fabric is sturdy and shows little sign of use, except on a strap where a would-be thief cut it. Lacking an awl, I had it repaired by a local cobbler.  The result was an insult to craftsmen everywhere and a triumph for entropy. Still, the hard used pack gives good service. I recommend it to anyone looking for a lightweight exceptionally comfortable and sturdy pack.

The result was an insult to craftsmen everywhere and a triumph for entropy. Still, the hard used pack gives good service. I recommend it to anyone looking for a lightweight exceptionally comfortable and sturdy pack.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

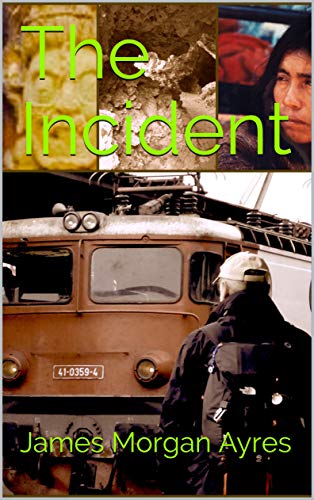

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Great story Jim!