Prologue

A road runs through the center of my heart. It begins near the English Channel and makes its wandering way to the Mediterranean, encompassing a good bit of my past and much that I hold dear. We followed that road together one summer, my son and I.

Justin was searching for his life’s direction and a road out of an unfocused, discontented adolescence. I hoped to find some fragments of my previous life along the way and piece together the shattered mosaic of me. While recovering from a severe illness during an eternal dark winter at high latitudes I had lost my sense of self, dragged my anchor and confused my bearings, or maybe I was simply losing my mind. I was drinking too much, even if it was good wine, the wolves were circling the cabin at night and that Ishmael mood was coming on strong. The geese had left for the south months ago. The cure was the road.

I had a few assignments, which gave our journey some structure, but mostly we let the road take us to little visited corners of Europe, to people who we hadn’t imagined and places we had never dreamed of, some of them wonderful, some surreal and others not on any map I have found.

We encountered a witch complete with familiars and the evil eye in a stone village near the Spanish border. A real witch? What’s a real witch? I don’t know. I don’t think I believe in real witches but whatever she was she scared us out of our wits one moonless night, turning us from our path and sending us back towards lighted streets and people with ordinary pets and cars speeding on the autoroute, touchstones of reality.

In Florence we met a circus strongman and the Countess who loved him, a woman I had once known who had married an Italian Count and everything that went with that, until she couldn’t take it any more. In Amsterdam at the very beginning of our journey a long forgotten lover again touched my life, a woman I had wronged. Maybe that’s why I had forgotten her and why it took so long to recall our days together in a village by the sea when we were young.

All this was before Prague and the former KGB assassin and before Justin threw the stowaway out the window. The vampire came later. I don’t believe in vampires either. But if such creatures exist in anything other than legends and flights of fancy I met one. A strange fierce woman who appeared in a fey moment during a soft rain next to the Dom in Koln where the Magi rest. She returned to haunt my dreams. I thought then they were dreams. Now I’m not so sure.

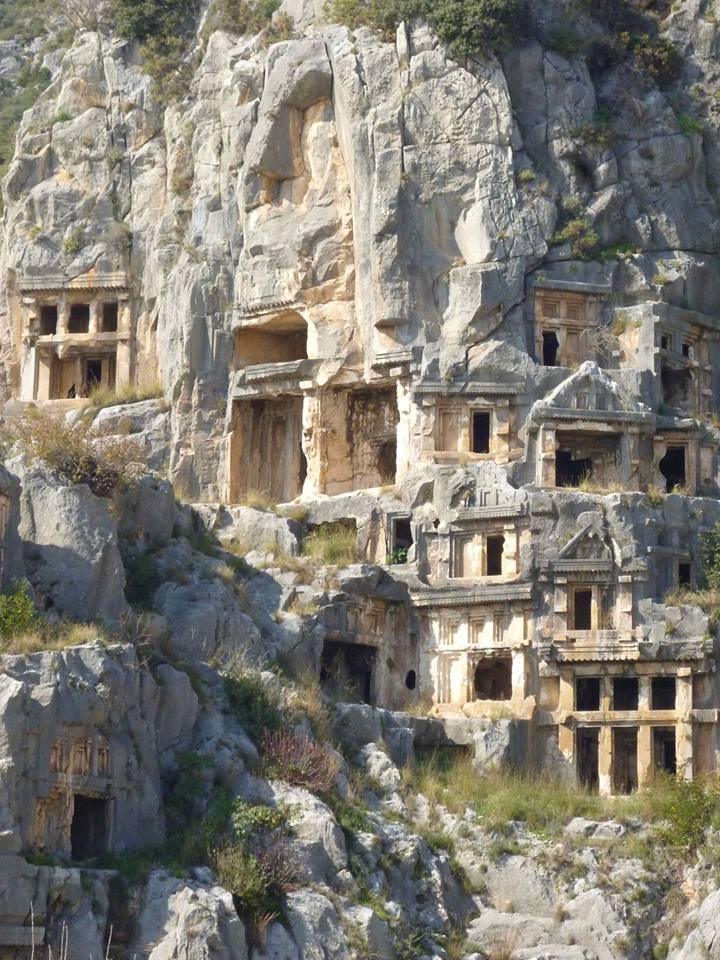

We got lost a time or two and had a few dark days. But we drank champagne from a bottle slashed open with a sabre, walked the stones of Roman roads laid down millennia ago and were transformed by music that brought tears to our eyes and joy to our newly opened hearts. We argued some and laughed a lot and drove each other more than a little crazy before we discovered our truest selves, and at roads end on the shore of an ancient sea each of us found what we had sought.

It has often been written that you take yourself with you wherever you go and that you will be no different in another place. In my experience this is not so, except in the most limited of circumstances and for the most limited of persons. People do change when they travel. It’s almost unavoidable. For many, change is the reason for travel. I think it’s in our blood. We’re nomads by nature and need to see what’s over the hill and around the next bend in the road, and we need to find that other self, that possible person, the one we might be, the one who waits for us out there somewhere.

Who returns unchanged from a journey? Only those who are unfortunately thick skinned and dense, or those who have been sealed inside the tourist bubble that imprisons would be travelers. If we travel with the slightest amount of openness and courage we cannot help but be affected by new surroundings and, at least in some subtle way, become a different person than the one who left home.

So it was for Justin and me. When we returned to wife and mother and sons and brothers we appeared the same. But we were not at all the same. If you would have looked very closely you might have seen that the two who returned were not the two who had departed, that we had changed in important and irrevocable ways. And that’s what our story is about; not only the places, but also things that happened in those places and the people we met and what it all meant to us.

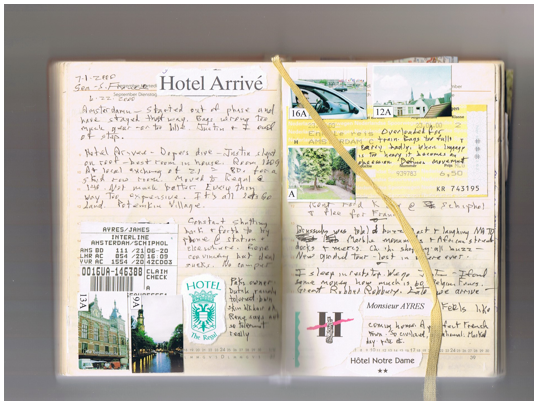

Prior to our departure I rummaged through trunks and chests until I found a pocket sized leather journal I had bought years before in a small shop in Milan. Its pages were fine cream colored rag paper and unmarked, the cover a soft tan leather darkened by the passage of time, an artifact from a former life and exactly the thing to record our journey. In the midst of chaos, straight lines on paper and words in a row can bring order and clarity.

In the Italian journal I pasted train tickets, restaurant receipts, small photos, crushed flowers, a feather from a blue jay, scraps of this and that, detritus of the road. I also made notes as events occurred. That journal became the foundation for this story. Some things may seem too fantastic to be believed. But as a working journalist I long ago learned to make accurate notes and to trust them. So I can tell you this; it’s all true.

In the interest of the narrative I trimmed a little here and stretched a little there. I also changed some of the names, for reasons that will become obvious. But I didn’t make up anything. Memory is fragile and mutable, and reality… Well, as anyone knows who has ventured out to the edge, the borders can get blurred. For me, it all happened just this way.

The Hotel Splendide

We escaped the mob by ducking into the lobby of the Hotel Splendide. A mud colored, beat up Formica counter squatted in the center of the room. To the right an open door led to a café. Dirty green linoleum covered the floor and rippled across the lobby like a storm-rumpled sea shot through with wrack and flotsam. Shabby chairs with crooked legs formed a conversational grouping with a sagging sofa. A half dozen twenty somethings in ragged jeans and t-shirts sprawled on the chairs and couch in states of consciousness ranging from dazed to comatose, none of them taking advantage of the furniture arrangement to make conversation.

A wasted brown dog lifted its head from the floor and half-heartedly thumped its tail. The air was thick with humidity and the greasy scent of rancid fried food seasoned with a hint of hash. It was unseasonably hot for early spring. A TV in the corner squawked about a low-pressure zone forming. Rain was coming. Maybe it would bring cooler weather. We were sweating, jetlagged and overloaded with far too much baggage. Rain sounded wonderful. Maybe rain would also clean the streets.

We hesitated inside the door, unwilling to go forward but reluctant to dare the streets again. Outside all was broken beer bottles and heaving crowds, pasty white men throwing drunken sloppy punches at each other and scuffling on the sidewalk. Thousands of them, slamming into each other and anyone in their way, jamming the sidewalks and streets, screaming and waving banners with the emblems of their soccer teams. One team had won. Another had lost. Apparently this was an extraordinary outcome.

Justin nudged me, “Is this one of those places where they sell hash and marijuana? What do we do if it is? Do you think Ash was here?”

Like many college age travelers Justin’s older brother Ashley had returned from Europe the previous year with tales of dope soaked Amsterdam, cafes with various types of weed and hash on the menu along with espresso and cappuccino, all fascinatingly legal and irresistible except for the espresso.

“Nah,” I said. “It’s just a hotel. A dump, but just a hotel.”

Due to the soccer mobs, football hooligans as the English call them, there was no room at any other inn. Trapped, we approached the registration desk and dropped our bags in front of the counter. A slight, rumpled man squinted at us with bloodshot eyes from behind the counter and asked, “Do you want some hash?”

Justin glanced sideways at me and smirked. Not one of those really annoying teen-age smirks, but still a smirk. A signal of my future parental trials on this trip?

“Ah, no.” I said. “Just a room.”

Mr. Ahmed introduced himself and leaned over the counter showing us a yellow-toothed smile, “You are English or Americans?”

His arms trembled and he was stretched thin to the point of transparency. Behind the counter was a much used reclining chair. I suggested that he would be more comfortable in his chair but he waved my concern aside.

I tried a smile in return and lofted him a softball, “We come from a country across the sea and far, far way in the distant west.”

He wrinkled his forehead, straining to understand, “What you say? From where?”

“California.”

“Ahh, you are Californias.”

“Yes, Californias.”

Mr. Ahmed’s arms were now openly shaking with the effort of holding himself up. He really needed to sit down and perhaps drift away on a magic hash carpet over minarets and green oases. But he was intent on business.

“You want only a room? No hash? I have Blonde Maroc, Afgan, Amnesia, many varieties. Best quality. Best price. Most serious stoning.”

“Can you get me on the Marrakech Express?”

Justin eyes popped. The smirk disappeared replaced by a look of alarm, which was something of an improvement over the smirk.

More forehead wrinkling and confusion, “What you say? Maroc? I have Maroc.”

“Just kidding.”

“No hash?”

“No hash.”

After much fumbling and confusion of papers Mr. Ahmed managed to locate a key. We followed him up narrow stairs covered with stained and faded red carpet, likely bought second hand from one of Amsterdam’s brothels. He stumbled and bounced from wall to wall as we climbed.

Squeezed together in the narrow staircase Justin whispered, “Is that hash, Marrakech Express? How do you know about it? Have you ever…?”

“Just an old song son, a train that left the station a long time ago.”

Mr. Ahmed opened the door to a room and waved us in with a slight bow, as if ushering rock stars into the George V. The narrow room reeked of dirty laundry, weed and hash. Plaster peeled from the walls. Rumpled linoleum covered the floor except where it had chipped away exposing splintery plywood. A bare light bulb hung on a frayed cord from the slanted ceiling. A small creature made scuttling sounds under one of the beds. The bathroom was down the hall and could be located by smell. Justin and I stepped into the room in stunned disbelief.

On a previous visit to Amsterdam, MaryLou, my wife, and two of our sons had stayed in a wonderful old hotel built in the shape of a triangle at the confluence of two canals. Our third floor room had a window on each side of the triangle’s apex. The floors were oak planked, scrubbed clean and waxed. Old timbers braced the white plaster walls and ceiling. It was like being in the bow of a sailing ship breasting slowly through thick leaved trees green as deep water waves. We hung out the windows on either side of the bow and waved to people passing in the streets and they smiled and waved to us, like dolphins who come to greet you when you lie on the bow of a fast moving sailboat.

For some reason beyond my understanding I hadn’t been able to locate that lovely little hotel. I had lost the reservations and couldn’t remember the hotel’s name. Still, I should have been able to find it. Once I’ve been someplace I can always find my way back to it. I never get lost. Yeah, I know, every male over the age of eighteen says the same thing. But in my case it’s true. Really. Somehow the location of our wonderful little hotel eluded me. It was a mystery.

That nice little hotel was then and this dive was very much now. It was this or a park bench. And our bags were a misery. In the store they had looked like just the thing: sleek, black, presentable in the lobby of the Principe in Milan or the Lotti in Paris. Then, like magic, unzip a zipper pull out some straps and you had a backpack suitable to climb Mt. Blanc. That’s what the salesman had said.

As packs they bit into our shoulders and sucked at our backs like monstrous leeches. As suitcases they wrapped around our legs and tripped us. Neither of us wanted to drag the miserable things another step. I looked at Justin. He mimed helplessness and shrugged. We dumped our nylon marvels on the narrow sagging beds. Dust rose from the bedspreads.

“We’ll take it,” I said, surrendering us to the luxuries of Mr. Ahmed’s Hotel Splendide.

* * *

Newly motivated we went in search of Charming Rene and his Camper Emporium. Rene would have our shiny Volkswagen camper waiting, sanctuary and mobility in one package. The VW camper is the Swiss Army Knife of vehicles. It can be parked anywhere you can park a car, gets good gas mileage and provides Spartan accommodations and cooking facilities. A home on the road without the overbearing presence of a motor home, the VW would allow us to travel unencumbered by hotel reservations or schedules.

We could free camp almost anywhere in Europe, often at the edge of a field, with the farm family coming to say hello and offering a glass of wine or beer, or at one of the free municipal campgrounds in the center of hundreds of French villages. Europe’s commercial campgrounds, frequently located in city centers, were islands of luxury undreamed of by American campers, with good restaurants, jazz bands, swimming pools and relaxed people on holiday and open to meeting new friends.

Around the corner from the Splendide I spotted a narrow building with a sign in the window: Vacancy. It was worth a look. The tiny lobby smelled of furniture polish and fresh cut flowers. The front desk was polished dark wood, the black and white tile floor shiny and clean. We could retrieve our bags and move here, forget about the room paid for in advance. The money spent would be fair ransom for our escape. I rang a polished brass bell on the counter top.

A round, biscuit colored man with a pleasant white smile came from a doorway behind the counter. He was neatly dressed in a green corduroy jacket and a buttoned up blue shirt.

“Good day,” he said. “My name is Mr. Banerjee. How may I be of service?”

I asked about a room. He had no vacancies. I pleaded, telling him where we were staying.

“I am very regretful,” he said. “I should have taken down the sign. I have not even the corner of a room. I don’t like to talk about my competition but I do understand how you must feel, being stuck at that place with your son. I know what goes on there. It’s all legal you know.”

Mr. Banerjee was happy to chat with us, but he couldn’t allow us to sleep in the lobby, which I suggested.

“The Dutch are very liberal you know, which is why I came here. I came first to Germany from India, but Germans don’t like foreigners, at least some of them don’t, especially if they have brown skin. One day, for no reason at all, a man said to me a word in English I didn’t know the meaning of. Later I learned that it was an insult word for a black man. As you can see I’m actually brown but I suppose that’s close enough for him to insult me. No one here has ever said such a word to me or made me feel as if I was being looked down upon. So I can’t actually complain when my neighbors take drugs. It’s their own business so long as it doesn’t harm anyone else.”

We said goodbye to Mr. Banerjee, and hurrying now headed for our appointment. Soon we would have our camper and be free from hotels. A sign, Camper Emporium, hung above a door leading into a white painted brick building, the office up a flight of stairs.

Rene came from behind his paper-stacked desk to shake hands, a tall man with expensively barbered blonde hair, blue blazer, gray slacks, and shiny black shoes. His handshake was firm, his blue eyes bright with good humor and fellowship.

He was waiting for a call from the garage. Our camper should be ready this afternoon, or tomorrow at the latest. We chatted while waiting for the call. I told him about our wretched hotel and our conversation with Mr. Banerjee.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Rene said. “I don’t think we’re so very much different than the Germans. Maybe we try a little harder to be accepting. Politically we’re a bit more liberal. I expect he just ran into a bigot. You can find them anywhere. We have bigots here in Holland also. Perhaps you have them even in America? Yes?”

The phone rang. Rene picked it up, listened for a few minutes and hung up.

“We’ll have everything ready tomorrow,” Rene said.

Our beautiful camper would be delivered as promised, serviced, waxed and ready to go. No need to bother with paperwork or details now. The sun was shining. We should enjoy Amsterdam today. Not to worry. All would be prepared for us. Tomorrow our wonderful adventure would begin. We would set out on the open road, wandering the highways and byways of glorious Europe, traveling as free as the wind. Rene was as charming in person as he had been during our transatlantic phone calls.

A thin woman with mouse colored hair, a lined face and a businesslike cardigan, and the harried but resigned look of the overworked, stamped and stapled papers at a desk near the door. She rolled her eyes at me. I should have taken closer note. Every successful small business has a woman at the center of it, a woman who knows what’s going on, does most of the real work and runs things while the men talk a lot and go to lunch. Clearly this was that woman.

On the sidewalk in front of the Camper Emporium Justin said, “Can I do it now? We have time. Come on Dad. You gotta let me. It’s Amsterdam.”

Justin had been nagging me for days. He was getting old. Life was passing him by. He wanted to dye his hair green, or bleach it. Or get a tattoo or get some part of his body pierced. Something. Anything.

“OK, you can do it.”

The shop was small, one upholstered chair for customers and two cane chairs for those waiting, a cabinet with the tools of the trade, blue and green striped wallpaper, white tile floor. Neat, clean, chic, it was perfectly suited to its owner. Freddy was slender and sharp featured, pale with straight blonde hair waxed and standing on end. He wore tight black jeans a starched white shirt and stood with one hand on his hip the other waving a comb back and forth.

“I simply won’t do it. No. No. No. Your hair is a wonderful natural color. I would have to strip out all the auburn and bleach it before dyeing it. And green is just impossible. It would ruin your hair.”

Justin’s frustration mounted. He pleaded, palms raised, “You gotta do something. I can’t come all the way to Amsterdam and leave with my hair all dorky.”

Freddy reached out and ran his fingers through Justin’s hair, considered the situation, “I’ll tint it and give you a great cut. With a red tint the highlights will stand out. It’ll be gorgeous. You’ll love it.”

I waited in the sidewalk café next door. Leafy shadows lay across the table. I had coffee and watched the street life, mothers pushing baby carriages along the brick walkway, men and women on black businesslike bicycles with bells tinkling.

“How does it look?” Justin said, collapsing in the chair across from me.

“It’s cool.”

“It sucks.”

“No, really, it’s cool.”

“I don’t know why he wouldn’t do what I wanted.”

“He probably cared about his work and wanted you to look good.”

“How about if I get my nose pierced?”

“Sure thing, no problem.”

“Can we go do it now?”

“Later.”

“When?”

“When you’re thirty.”

A deep sigh, shoulders slumping, “Can I at least have a beer? It’s legal here.”

As we talked Freddy came out and locked the door to his shop. I waved. He dropped a black canvas shoulder bag on a chair and ordered a Kir from the t-shirted waitress.

“I know you’re disappointed,” Freddy said. You wanted that surfer look. Are you a surfer?”

A rueful headshake from Justin, “No.”

“Are you planning to be a surfer?” Freddy asked with a raised eyebrow, his head tilted slightly to one side.

“Not really. It’s just a look.”

“I remember being a teenager. It’s tough. But just be who you are. Don’t worry about looking like anyone else.”

Freddy had been born in Amsterdam and had traveled all over Europe and to San Francisco and Bali. We shared reminiscences about the beaches and bars and some of the weird scenes in Bali. Justin sipped his first legal beer, listening with one ear and watching the young girls in jeans walking by.

“Do you like that beer?” Freddy asked.

Justin shook his head, “Not really. It’s bitter.”

“Why drink it? Life is too short. Order something else, on me.”

We talked travel, art, music, and fashion among young people, a topic on which Freddy was an authority. After a pleasant hour Freddy waved goodbye. As the day started to fade Justin and I wandered away from the center of town and into a neighborhood of narrow three story homes, quiet streets and arched bridges. We ate dinner in a tiny patio restaurant; cobblestones under foot, red brick walls overgrown with ivy, curlicued iron tables with thick white tablecloths, a handwritten menu. The crowd was local, artsy, much laughter, loud greetings and cheek kisses.

From a nearby table a woman watched us closely, her hair the color of India ink and skin pale as a winter moon. She was dressed all in black with a slash of blood red lipstick. Her eyes were shadowed under deep brows. Twilight crept over the patio. She watched us with intensity, first focused on me, then on Justin, her food forgotten, absently talking with her table companions and watching, watching. I couldn’t imagine what drew her attention, an ordinary man, a teenaged boy. Did I know her from someplace, a show, an opening? I considered going to her table but I was tired and not that curious.

The food was… Dutch. Amsterdam, after all, is not Paris, or Rome. There was a fillet of white fish that had been successfully grilled, some boiled potatoes and a carafe of straw colored wine, nothing really to complain about. Excitement and wild abandon at the table would come later, further south. On second thought, who was I kidding? This was a better meal than I would have found in all but one or two restaurants within a ten-mile radius of my home in Southern California, where we get a good deal of pretension but very little good food, unless we’re willing to pay an absurd amount of money for a simple meal.

Justin ate quietly, his eyes busy, watching the other diners, many of them in their twenties, young enough for him to see himself in them. I wondered what he was thinking. Was he remembering a childhood journey across Europe, wishing he was at home with his girl friend, wishing she were here?

From the next building came the faint sound of music, Janis Joplin singing her life away, a little piece of her heart at a time. Her wrenching gut strong voice seemed out of place. Amsterdam was smoky jazz clubs, Django Reinhardt’s gypsy guitar, Chet Baker’s drifting moody sax. Baker had died not far from here, falling from a high window, or pushed rumor had it by a heroin dealer to whom he owed money.

As we were leaving the woman who had been watching us contrived to pass close by. She wore a floral scent and her skin looked soft to the touch. Her eyes were dark indigo with flecks of violet and that watchful intensity.

“Have we met? I asked.

“You don’t remember?” One eyebrow raised, a tone of mocking indignation.

“I’m sorry. Who…?”

A small shrug of one shoulder, a moue, “Memories fade. And anyway vous semblez perdu.”

She turned away, leaving a slight cloud of perfumed air and a name for the scent drifted into mind, L’ Air du Temps. She walked down a narrow hallway and looked back, a small wave over her shoulder, chin down, eyes slanting up to mine, “Au Revoir.”

Maybe she was right. Maybe I was lost. Not a flicker of memory came to me. Paris? The way she held her body, the way she moved, her accent, all said French. Certainly she didn’t have a Dutch woman’s straightforwardness. Her manner suggested something more than a casual contact. I searched through distant memories, still nothing. Early onset Alzheimer’s? One of those Sixties things where the things you were doing made you forget the things you did?

We avoided main streets where the mobs still roamed and walked slowly, neither of us anxious to return to our garret. Justin scooped up a handful of pebbles and we sat on the edge on a canal, dangling our feet as he dropped the pebbles one by one, sending smooth ripples across the moonlit water. I remembered a summer night when Justin was eight and we had sat together on the banks of the Seine until near dawn watching the riverboats and the life of Paris at night. He had held my hand as we walked back to our hotel stopping along the way to look in the windows of toy stores.

The years had changed us. I didn’t laugh much anymore and Justin had entered the foreign land of the teenager. We were no longer as close as we had been. He was not sure about this trip, not sure he wanted to travel anywhere with one of his parents and was angry at leaving his girlfriend. MaryLou and I were secretly glad about the separation. The two of them had become entirely too humid and hermetic.

Eventually we trudged back to the Hotel Splendide and up the narrow stairs. A haze of hash smoke drifted from an open door and hung in the hallway. A procession of young Americans stumbled from their room into the hallway and to the communal bathroom and back to their room. From their room came howling, yelling and thumping. They were all muscular and healthy looking. Maybe they were a mixed soccer team from some Midwestern liberal college come to play in the ongoing games.

One of them bumbled down the narrow hall towards us holding out a pipe. He had long blonde hair and the loose muscled walk and manner of a good-natured Golden Retriever. “Have some hash,” he said. “It’s really good shit.”

I held my breath, fighting off a contact high and hoping Justin was doing the same. What were they were mixing with the hash? That much dope they should have been comatose. I was anxious to get Justin out of the smoke cloud. I smiled and mumbled something and shouldered Justin into our room. Justin stumbled against the bed and said, “You don’t have to push Dad. I don’t want any of that crap.” Smoke crept through the cracks around the door and seeped under the walls where the floor was warped.

Justin swung the dormer window open and crawled out onto a wide roof. I followed. A fresh breeze swept the roof. City lights formed a hazy yellow dome over us, stars shone dimly. We dragged our mattresses onto the roof and sat cross-legged watching the city at night, lights shining from apartment windows, a couple walking below holding hands.

Justin was restless and wanted to roam some more. It was midnight but I sensed some secret mission he wanted to carry out on his own. He needed me to trust him and so I let him go with a promise to return in an hour. I started pacing the roof a minute after he was gone and torturing myself for letting him roam alone at night in the streets of this city. There was a nasty underbelly to Amsterdam’s openness. It was his first night on his own in another country. I told myself that I had to give him some room. He was fifteen now. But he was the baby, the youngest.

Some years ago MaryLou and two of our sons had spent the summer jumping on and off trains from one end of Europe to the other. Justin had held hands with each of us in turn as we raced through stations to catch our trains. As we left each station I stopped the boys and had them turn and look at the front of the station buildings and again when we were some way from the stations. In this way they could see where they had been and be able to find their way back. If separated we would met at the information desk.

In a small town in Denmark Justin had so blithely and happily ignored my instructions I was sure he wouldn’t be able to find his way if lost. He was so happy and in the moment I was reluctant to intrude, but parental duties over rule all. I stopped him at the end of the platform and said, “I bet you don’t have any idea where you are.”

He thought for a moment and then replied with full confidence, “Oh yes I do.”

“Tell me then,” I said. “Where are you?”

He beamed, triumphant, “I’m with you.”

But now he was not. The promised rain came at 03:30. I brought our mattresses inside.

Next door the Americans were yelling and slamming into walls. Our empty room reproached me. Justin’s things were spread across his bed as if his bag had exploded. I was a rotten parent. Justin had been sheltered by the closeness of our family. He was not as streetwise as his older brothers. Anything could have happened. Maybe he decided to experiment with some of the readily available drugs. Christ, you could buy heroin on any corner. Maybe he got mugged. Where could he be in this rain? I was an idiot. I should have followed him. He wouldn’t have spotted me but it would have been a violation of trust. I couldn’t wait any longer. I grabbed my jacket and clattered down the stairs. And ran into Justin on his way up.

He was soaking wet, his face flushed, “I got kind of lost.”

“You got lost?” Justin had later taken my route finding lessons to heart, as had his brothers. They could find their way through any city or unknown forest or mountains.

“Yeah, I know. But it started raining and my glasses got all fogged and wet and it was dark and then there were some weird crazy people and I got confused and…”

“Never mind. Lost is going around. Were you scared?”

“Maybe a little. But then I was OK.”

Justin hung his wet jacket on the edge of a door and moved his things to the side of his bed. He sat with his back against the wall and his legs folded. He wanted to talk but was nervous. I had to be cool. No heavy parent stuff. Finally he started and was able to tell me about his nighttime adventure. He had been on a mission of his own. At first he was embarrassed then it started coming easier.

“The women were sitting in rooms with big windows and almost no clothes on. Really. It was just like everyone said.”

I sat on the edge of my bed and took slow deep breaths, nodding, noncommittal, “Uh huh, right, and then…” The party next door continued with much squalling and yowling and banging like they were kicking over the furniture and taking turns beating each other with a sack full of cats. Maybe they were practicing for an athletic event or engaging in vigorous group sex, anything seemed possible. More smoke seeped under the walls. Someone yelled, “Motherfucker!”

“There was one in a red corset thing with garters and stockings and the lamp had a red light. In another window one was dressed like she was in a grade school uniform with a blazer and a pleated skirt and pigtails. But then she flipped up her skirt and she didn’t have any panties. There were windows all along the street and all of them had a woman sitting or dancing or reading or something. There were doors where you could go inside and some of them were fat and not pretty at all, and old too. Some of the windows had curtains pulled so you couldn’t see. Why do you think the curtains were closed?”

“Maybe that meant that they weren’t available,” I said.

“Oh. Like she was with someone? You mean like actually just doing it in the window behind the curtain.”

“Or maybe she just went out for coffee or something.”

“They weren’t all in windows. Some were walking or standing around. One of them came up to me and asked me if I wanted to go with her. She opened her shirt and showed me her breasts.”

“And you said?” I’m still pretending to be the blasé parent while mentally yelling at myself, “Stupid, stupid, stupid!”

“Dad! She was old. Maybe thirty. How could she come up to me?”

“Well, maybe for her business is just business.” Still trying to keep calm. “Was she pretty?”

“No. Yes. I don’t know. It was just so weird. Just the idea. That she would… really would… I mean with anyone. Just for money.”

“What did you say to her? You weren’t rude were you?”

“I didn’t say anything just shook my head and kept walking. Why?”

“Women in that position are especially vulnerable. Never say anything hurtful.”

He needed to talk and so I let him get it all out. He had imagined some erotic fantasyland, but the gritty reality of commercial sex had wiped away his illusions.

“She smiled at me. But not really. She wasn’t really smiling, not a real smile.”

The rain stopped. The racket next door had died down, but the air reeked and we agreed that we felt like we were locked in an insane asylum. We drug the mattresses to the roof again found a dry spot under an overhanging eve and fell into the sleep of escaped prisoners.

I dreamed of Justin lost and wandering in dark streets with shadowed shapes looming at him, of a bare breasted woman with red nails, sharp eyes and a false smile following him. Then I too was lost in the winding streets in a strange city. My wife was far away and my sons all lost to me. And then my dream self remembered that I was only traveling and that my family was safe and well. I awakened and saw Justin curled under a blanket the city quietly humming around us, and knowing that all was as it should be slept without dreaming.

* * *

Morning, a clear Delft sky and small storybook clouds. I sat up and stretched. Across the street an open window into a high ceilinged room, white walls, blond wood and skylights, a perfect artists atelier, and a girl in her late twenties with long honey hair and pale skin. She waved and smiled and we called, “Hello,” to one another. I watched her making coffee in a tiny modern kitchen until the smell of fresh bread drew me to the front of the roof where I looked over the edge. A thin man in a ragged overcoat slept on the sidewalk, scabby ankles, run over shoes. Across the street people were leaving a bakery with white paper sacks.

In the room Justin was showered and ready to go, “Hungry,” he said, “Hungry, hungry. Need food. What do they eat for breakfast around here?”

“Creamed herring, jellied octopus, maybe some cold liverwurst, not much else,” I said.

“Yeah. Right. I smell the bread.”

Mr. Ahmed ambushed us as we crossed the lobby. “Have you pay for your room?” he asked, forehead wrinkled, eyes squinting, querulous.

I produced my scribbled receipt. He held the scrap of paper up to his face. His eyes looked like they were going to start bleeding at any moment. Something like relief appeared. His wrinkles smoothed. His voice was almost hearty.

“Ah yes, of course you have pay. You are the Californias. You are gentlemen. It’s the others who try not to pay. You like your room?”

We went through this routine every time he saw us cross the lobby. Mr. Ahmed was totally stoned at all times but well mannered and pleasant. I didn’t have the heart to tell him we were sleeping on his roof.

“Lovely room,” I said. “Very atmospheric. Memorable.”

“Would you like some hash? I have new shipment. Very fresh.”

We fled before he got further into his sales pitch.

I wondered what errant tide had brought this frail almost used up man to this place. Powerful currents of humanity’s global sea were washing people up on all shores, changing lives and continents in a vast roil that showed no sign of ending. What had brought Mr. Ahmed and Mr. Banerjee, two so very different men, here to this red brick city where the sea was held back from sweeping it away only by diligent effort? What events in their lives had led them each to the same city geographically, but to worlds so far apart they may as well have voyaged to different continents?

Mr. Ahmed was a Muslim from Pakistan. He had no involvement with or interest in any religious or political activity that I could see. Only if a bill came before the Dutch high court to outlaw hash could I imagine him rousing himself to action. He appeared to be focused entirely on his next hit of hash and on moving enough product to make that possible as a continuing way of life.

Mr. Banerjee was Hindu. He didn’t eat beef, but other than that had little or no interest in the religion of his birth and no patience whatever with religious fundamentalism. He was making a decent living and raising his daughters to be western. “All nonsense, that stuff about keeping women locked up,” he had said. “Fearful ridiculous men.”

After steaming café au lait and croissants at the bakery we walked the few blocks to the Camper Emporium and climbed the stairs to Charming Rene’s office.

“Your camper is ready for you,” Rene said. “In fact you have your pick of three. They are all in excellent condition and waiting for you to choose.”

The thin, serious woman by the door pressed her lips together, caught my eye and shook her head slightly.

Rene drove us to a storage lot in his Benz. The sky turned grey and started leaking, first a fine drizzle, then opaque sheets dropped over us as we sped through the semi-flooded streets. Rene parked inside what appeared to have been a World War II airplane hangar. We waited beside an open door for the rain to slacken looking out over a large muddy field scattered with various cars and trucks. The sky ran out of water and Rene led us to the far side of the lot stepping carefully in his shiny shoes.

Three VW campers slumped forlorn and tired, facing each other in a small huddle. One of them had once been bright orange. Now its brave color was faded and blochey. Rust edged the driver’s door and rocker panels. We climbed inside and I slipped the key in the ignition. Justin adjusted the mirror so he could inspect his new haircut. Foam poked through the upholstery. The starter ground a couple of times before the battery gave up.

The next one had once been white, now scabrous with rust. The rain started again. We ducked in the side door and sat in the rear seats. Rain dripped into a puddle in front of the cabinet that housed the stove and sink. The upholstery was worn thin and water stained. Everything smelled of mold. The puddle grew deeper.

The third camper leaned to one side with a broken spring. Its windshield was cracked. The side panel had a long deep crease. It was a broken relic. I didn’t have the heart to try and start the poor thing. None of them looked like they had ever had a good time with a happy family. Or if they had it had been long ago and since then they had been run hard, abused and abandoned.

“Yes, that’s right,” Rene said. “A full bumper to bumper warranty covers absolutely everything, except the engine and transmission. Oh, and the brakes. Guaranteed for a full week anywhere within fifty miles of Amsterdam.”

“But we’re going to France and Spain and Italy.”

Rene smiled a brilliant, cheery smile. “Completely worthless isn’t it,” said with a confidential air.

I remembered our shiny new VW camper when the boys were little, the California coast, splashing in tide pools and wandering our way up the coast to Vancouver and then back south through the Sierra. We were supposed to be on the road for Paris today.

“I think the white one is best, don’t you?” asked Rene. “I’ll have it cleaned up and serviced for you. It will be perfect. Tomorrow the sun will be shining. You will have your home on wheels. The road awaits you.”

Charming Rene agreed to wait for us in the hangar while Justin and I sat in the white camper and talked, the water from the wet seat seeping through my pants.

“What do you think,” I asked.

“Dad? Are you nuts? We’ll be on the side of the road somewhere in Spain with a blown engine.”

“But what about the trip? We’ll have to run from hotel to hotel. Summer crowds, no rooms, you remember. It’ll be totally different than we planned.”

“We have the sleeping bags and the tarp.”

We had packed ultra light sleeping bags and a tissue weight nylon tarp in our miserable luggage, planning to use the sleeping bags in the camper. The tarp would serve as a sunshade or “just in case.” It looked like “just in case” had arrived.

“You OK with that? A tarp in the Sierra is one thing. Europe is different.”

“Don’t get this sorry wreck for me. I’ll be OK. We can still stay in campgrounds.”

True, we could. Free camping would not work without a camping car, and then there was the thought of the hard ground and my old bones…

“It won’t be what I wanted it to be. I wanted the trip to be…”

“Dad, you told me a hundred times, ‘It’ll be what it’ll be.’”

Wisdom from the young, words I had forgotten. I was pushing too hard.

“You sure?”

“Dad. Are, you, nuts? Let’s get out of here.”

We left Charming Rene at his office and returned to the hotel for our bags. Mr. Ahmed waved goodbye to the Californias from the threadbare couch in the lobby. The rental agency was next to the train station. I gave the girl behind the counter a credit card and twenty minutes later we were in a tiny mussel-shell of a car with the awful bags in the trunk.

We fled through the streets of Amsterdam as if werewolves were snarling at our heels. I hit the on ramp and got my foot down and kept it there. The omens were not clear. We had no camper and no sure plan. But no matter, we were headed south and the sun was breaking through. We were on our way.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End