On a sunny morning in early March, ML and I left Istanbul on a comfortable air- conditioned bus. We traveled to the Bulgarian border over smooth four lane freeways running through rolling hills and fields of grain, stopping at rest areas with fast food restaurants and clothing outlets. If the signs were not in Turkish you might have thought you were in Midwest America.

On a sunny morning in early March, ML and I left Istanbul on a comfortable air- conditioned bus. We traveled to the Bulgarian border over smooth four lane freeways running through rolling hills and fields of grain, stopping at rest areas with fast food restaurants and clothing outlets. If the signs were not in Turkish you might have thought you were in Midwest America.

Crossing the border from Turkey to Bulgaria was like entering a war zone where the fighting ended twenty years ago but the survivors didn’t bother to clean up. The first buildings I saw looked like they’d been hit with 106s and raked with .50 caliber fire. The next row of buildings had been patched with debris from neighboring collapsed structures. The main road leading from the border was a two-lane track, potholed and crumbing, jammed with big rigs blowing oily diesel smoke and contending with our bus for right of way. Then came miles of abandoned industrial buildings with broken windows and collapsed roofs. Rusted machinery like husks of gigantic alien insects littered factory yards. Junked and burned out cars lined the streets of beaten villages where gray people in ragged clothing shambled listlessly along muddy lanes.

The first person who spoke to me in Bulgaria was a beggar at the bus station in Plovdiv who aggressively demanded money, cigarettes, something, anything. The second was a clerk at the bus station who snarled when I asked to buy an apple and threw my change at me.

We arrived in Sofia, the capitol city, in late evening. A cold wind shifted foot deep drifts of trash along dark streets with broken pavement. The few streetlights that worked threw dim yellow light in small pools. Graffiti covered standing walls of partially demolished buildings. Bricks and debris spilled onto sidewalks and into streets. Vacant lots were piled high with plastic bottles, cardboard boxes, rusting auto parts, mounds of unidentifiable trash and stinking garbage.

Sidewalks were shattered, and between tilted slabs of concrete deep holes in the pavement awaited the unwary. Feral dogs roamed free. A pack of five watched us, pacing us for a block or so before fading back, perhaps in search of easier prey. The local news frequently reports stories of people being attacked and savaged by the dog packs. Some are killed.

Mafiosos drive BMWs and Benzs and were everywhere with black leather, shaven heads and giant muscles from years of extreme weight lifting and steroids, faces and scalps covered with ‘roid rash.’ Restaurants had signs prohibiting guns and knives at the door; which I took to mean that everyone was carrying one or the other, perhaps both. I have since read that the center of old town Sophia is spruced up for tourists. We didn’t see it. We were too busy keeping an eye on the dog pack as we searched for a place to eat.

No one smiled or spoke when passing. People walked with downcast eyes; they probably go from home to work and pass people they know on the street and not see them. Public discourse was rude and surly. When I responded to scowls with a big smile and a cheery ‘Dobra Den’ I got sideways looks of alarm and a flash of bared teeth.

I read that Bulgarians regard smiling in public as an act of weakness. A friend, a Romanian who lives in Germany, advised me to not use my bankcard at any outside ATM, or to use it in payment for anything. ‘Odds are high it will get hacked. Happened to my wife. In Bulgaria cash is best – if you’re strong.’

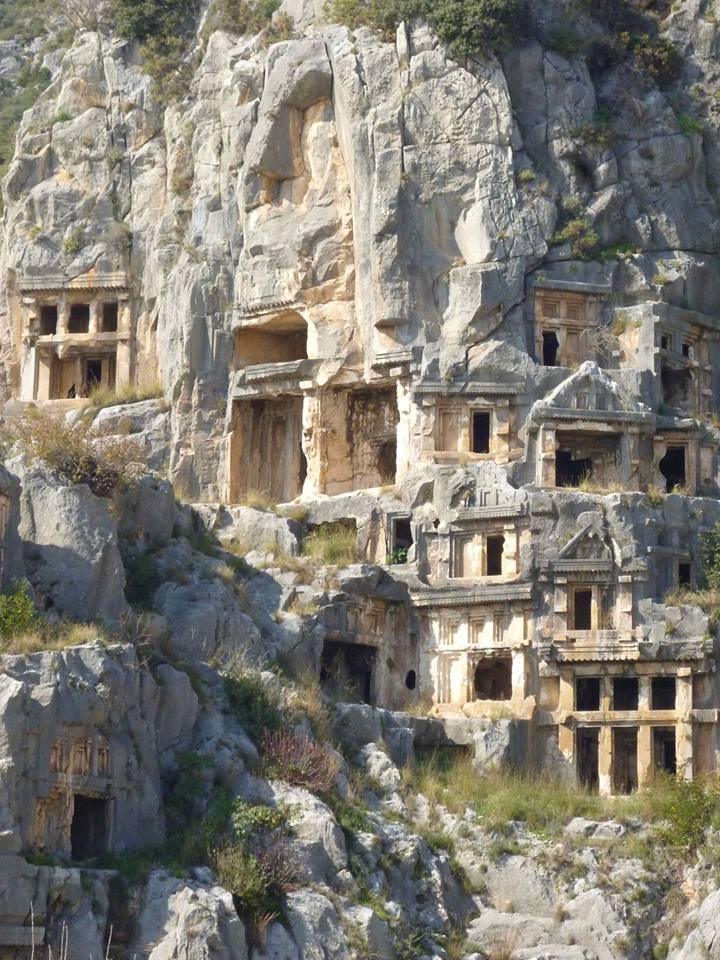

North of Sofia young pine trees cover the mountains, new plantings, an attempt to recover from decades of Soviet clear cutting. We stopped for the night in Veliko Tarnovo, a transportation hub and charming medieval hilltop town with a castle and crumbling walls and a street with new shops filled with fashionable clothing for skinny young girls. True, the biggest business on the main street was a casino with ‘live girls,’ and there were more sex shops than bookstores. But there was one English language bookshop, an outpost of civilization.

The next morning we took a cab to the the village where we were to live for some months. It was a long drive. Much longer than we had been told to expect. The trees were bare and the earth had been plowed, ready for planting. The turned furrows looked rich and dark, the kind of earth where, as the saying goes in Mid-West America, ‘you can throw out pebbles and grow boulders.’ A small river ran parallel to the road, the water rimmed with ice in eddies. A roadside shack displayed fox skins for sale.

Our host failed to meet us at the center of the village as planned. The village commercial center consisted of one muddy street littered with trash and scuds of blackened snow, a block of dilapidated and shuttered buildings and a low building at the end of the block that appeared to be occupied, apparently the local ‘café.’ The wind blew cold and brought the scent of sewage.

Inside I found a claustrophobic room with paint peeling from walls, filthy windows and floors and men in ragged clothing drinking raki at mid-morning, engulfed in clouds of cigarette smoke and smoking as of they were getting paid by the cigarette. I inquired after my host by simply repeating his name. One of the men pulled out a cell phone and made a call. Then he said my host’s name and shook his head, as if to say no one knew him. It was later that I recalled that in Bulgaria a head shake means yes, a nod means no.

In search of my host I located the one other building in town that appeared to be inhabited – the front door was open – a two-story concrete building that had once been painted yellow. Now the cheery paint was a faded memory and the building in the early stages of decay. On the ground floor I found a one room village store with a glass case containing scraps of mystery meat, one half empty box each of wormy apples and sprouting potatoes, a shelf of vodka and raki and two enormous cold cases filled with beer. The storekeeper pointed up the stairs and said, ‘Mayor. Mayor.’

The concrete stairs were grimy and ankle deep in trash, spider webs grew in every corner. The corridor at the top of the stair was empty and cold. There was no heat in the building. One door was open a few inches, the others padlocked. I pushed open the door. It creaked on rusted hinges. I called out, ‘Hello. Dobra Den. Anyone here?’ The mayor appeared to be out of the office.

Back outside I walked the puddled village lanes calling my host’s name. Mud brick walls surrounded all houses, dogs chained up and howling. The glimpses I got of houses over the walls revealed ramshackle buildings built of sticks and mud bricks. Plastic beer bottles choked a half frozen steam. A three story abandoned school with broken windows and missing doors slumped on a desolate corner lot. A grizzled man in a donkey drawn cart passed me on a narrow lane, the donkey kicking mud in my face. I smiled and waved and received a scowl in return. Finding no one who seemed to know my host, or anyone inclined to help an obvious stranger, I returned to the center of the village.

It was time to bail, head back to Veliko Tarnovo – the nearest inhabited town. It was the only way out of here. The cab had long since departed, our cell phone wouldn’t work, and we spoke no Bulgarian. I figured we could persuade someone to call us a cab or give us a ride back to VT by the simple expedient of waving some cash and repeating the word taxi and our destination. It’s worked before in a dozen or so countries. Why not here? Taxi is a universal word. So is cash.

Before I was able to put my plan into action, our would-be host called to us from the end of the street. He seemed to think that local conditions were just dandy and asked us to follow him to his house. We hesitated. Bulgaria did not appear to be place of joy. Fifty years of Soviet occupation are written in the lines of faces, in people’s posture, their manner, their inward turned presences. Go or stay?

First impressions are only definitive if they go to the heart of the matter. Maybe there was more to Bulgaria than we had seen. I could show you parts of America with miles of abandoned industrial buildings, boarded up stores and falling down buildings. I could show you winos drinking from brown paper bags in parking lots of steel barred liquor stores and prostitutes in spike heels and short skirts on corners next to schools, gang bangers dealing dope and cruising in new cars and kids playing in trash filled vacant lots. In America I could show you despair in the eyes of old women in ragged clothing pushing shopping carts.

We don’t travel only in search of golden beaches and awe inspiring mountains. If we stayed, maybe we would find hidden behind scowls and mud brick walls something more precious than well-ordered streets. Maybe we would find the Bulgarian heart.

ML and I looked sideways at each other. I raised an eyebrow. She shrugged. I nodded. We picked up our rucksacks and headed down another muddy lane.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End