Building With Stone

Here men build with stone. All around us are stone walls, steps, plazas, verandas and houses. Over the past weeks I’ve watched two men building a stone wall on the road leading up the hill to our house. They patiently chip away at large blocks, rounding or flattening them to fit into the space between the last stone they laid and the next one they will place. They wear slouch caps and worn clothing and have hands rough as the stone they work.

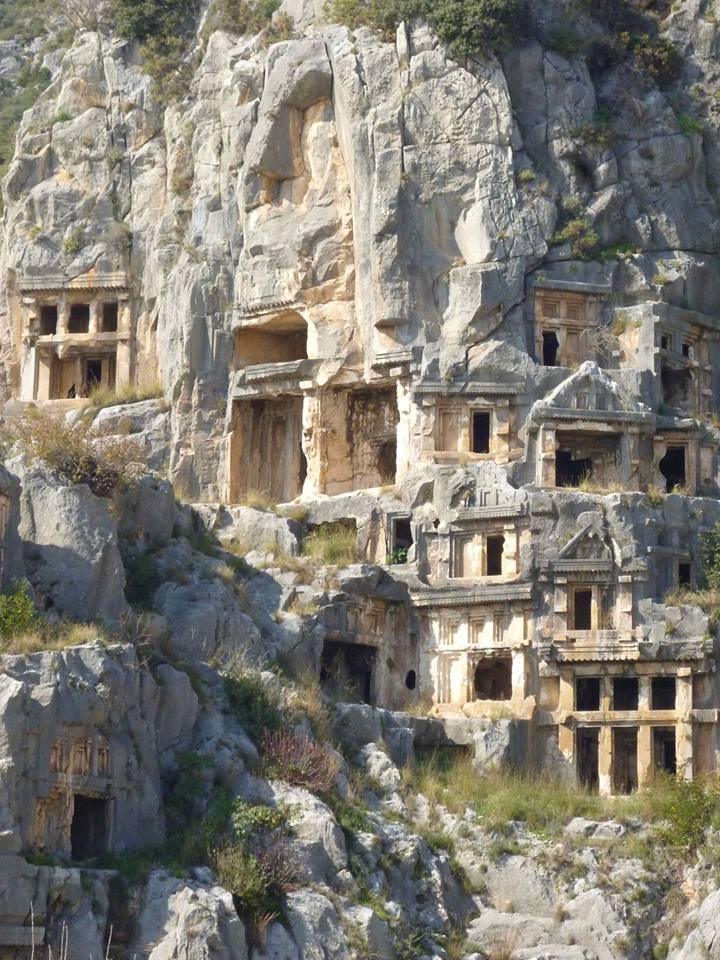

In the Ottoman Empire, men built with stone. They built monuments to their rulers, castles to protect them, and fantastic religious architecture, with minarets piecing the sky so God could hear their prayers, and so the muezzin’s call to prayer could be heard by the faithful. The cry of the muezzin has echoed from these hills for a thousand years, but is itself a new song in this ancient land. In Byzantium, before the Ottomans, men built with stone. They built monuments to their rulers, castles to protect them, and fantastic religious architecture, with bell towers which rang for a thousand years to call the faithful to prayer.

Before the Byzantines were Romans, before them were Greeks and Lycians, and before them were others, going back to long, long before the beginning of what we call civilization. To the east, men built gigantic stone monuments twelve thousand years ago, the oldest man made structures yet discovered. Little is known of those people, except that they hunted, gathered, built, lived.

We came to this ancient land seeking sanctuary from pettifogging bureaucrats; travelers in our new world order are now forbidden to stay in many countries for more than ninety days. But rarely do we travel only from things. We travel to – to see around the bend in the road, over the next mountain, across the sea. We travel to see how life is different in another place, what magic resides in another land. Long have I wanted to visit this land where so much began, where travelers and traders crossed paths with mystics and madmen, where wars were and still are fought, civilizations were founded and fell, and where men walk footpaths laid down centuries ago.

Here in this tiny village on the side of a steep hill next to the sea, we found a way of life that has almost disappeared from Western Europe, one that has entirely disappeared from America. In our village, each house has a small plot of land, on which the people plant and grow: grapes and olives, lemons, oranges, figs, eggplant, tomatoes, arugula, cabbage, three kinds of peppers, onions and almonds. Everyone has chickens, which cluck about, pecking at insects. Goats are tied out on long ropes to crop weeds, and gathered into pens come evening. Some houses have a cow or two. There’s a carpentry shop, a small general store, a school, a mosque. Traveling traders drive their vans along the graveled streets cut into the hillside and honk to announce their arrival and wares. Dogs wander freely, as do cats.

Our neighbors knock on our door and bring us produce from their gardens, olives they’ve cured in tall jars, fresh eggs, rolled and stuffed grape leaves from their kitchen, home baked cakes and cookies. ML cooks and sends out dishes of her creation in return. A man at the end of the road has a chainsaw. He delivers sawn logs to our next door neighbor, who splits them with his ax and gives back some of the split wood in payment. Matrons in brightly flowered baggy pants and head scarves carry two liter jugs of goat’s milk to their neighbor’s houses and return home with freshly baked bread.

Some villagers hark back to their nomadic traditions by nurturing and culling the tourist herd during its annual migration each summer. Kas is a few kilometers from our village, a charming town structured like a sheep shearing operation. The main street is a long stock chute, much like any livestock chute designed to channel the sheep, cows, or goats to the waiting farmer. The main street runs downhill, lined on each side with pensions, shops and cafes. The tourist herd enters Kas at the top of the hill and makes its way down towards the harbor. The slow, the hesitant, the outliers are the first snagged by charming merchants as they pass various enticements, but eventually all succumb, and are sheered clean as any spring lamb.

Feeding, watering and amusing a few thousand head of tourist each summer provides cash for cars and computers, for new stoves and additions to houses, and to send children to school in far away universities. But roots in the village remain strong. Few here bend the knee to corporate masters. The local enterprises are in fact local, and the way of the grape and olive continues.

A nearby village is peopled almost entirely by nomads. Each spring they vacate the village here overlooking the sea, and move to a mirror village high in the Taurus Mountains. Entire clans move together, crowding into vans, or walking, taking with them their goats and camels. At the high village their cherry trees bear fruit and they plant summer gardens and pasture their goats. In autumn they move back down the hills, their almond trees in the lower village now drooping and ready to be picked.

The few expats here smile at one another, sharing a secret they have discovered – that this older way of life is a better one than the one left behind: acrimonious and mean spirited public dialogue, bleating horns, jammed freeways, sixty hour work weeks, wall wide television screens, malls and shopping and subliminal and relentless pressure to buy, work, hurry.

Here we’ve met a formerly famous actress who won’t own a television and gave walk-in closets filled with designer clothing to charity before pulling the plug. We’ve met former school teachers and soldiers, corporate refugees and escaped employees of all kinds who have given up cars and suits and who walk to the farmer’s market each week. Even though many pinch pennies, all have time to watch each splendid evening fold in on itself as the sun turns the translucent water into Homer’s wine dark sea.

I have a friend, a dear friend, who now lives on a cliff overlooking the sea in a tiny fishing village in Japan. In our younger days we both lived in the fast lane, in the worlds of entertainment and high fashion, glamour and glitz, bright lights and first class flights. My friend came to his Japanese village by a long, circuitous and hard fought route. At the end of that journey he found peace and contentment in a simple life. He takes pleasure and sustenance from the sea and fishing, from his garden and the work that goes into it. He rises with the sun and takes time to watch the sea in all its moods, time for reading and long slow evenings, things for which he never before had time. He wonders what all the hurry, all the fuss, was about for all those years.

Until now I had not ever experienced the kind of life my friend describes to me in his letters. I understood it, I thought. But that life was not for me, I thought. I see now that I did not understand it at all. I also see that life is for me – for now. I am content here. I treasure each day in this village above the sea. But still, I wonder what lies over the horizon.

We came seeking sanctuary, a place to live until we could return to Europe. We found a way of life older than the dry stone walls that line the roads, older than the inscriptions on the tombs telling of mighty men, now forgotten. We would like to stay a little longer to know better the people here, to learn more of this life. But the octopus with its ninety-day rules has insinuated its tentacles even into this forgotten corner.

When the authorities call time on our stay here we’ll do what travelers do. We’ll move on, wandering from country to country till we tire of travel, or until they slam the last door, turn the last loophole into a noose, and nail down the last nomad, the last bohemian, the last gypsy, the last wandering minstrel. If the universe allows, we will return.

Stone monuments, tombs and cities litter the countryside hereabouts, their edges softened by age, their inscriptions worn and unintelligible. One of the oldest senate buildings ever constructed lies in nearby hills, a tumble down pile of stone until the restorers got to work and turned it into a beautiful replica of its former glory, a tourist attraction. This seat of government was once the heart of a proud city – now only ruins where goats graze. Monuments crumble and stone wears away. Bureaucracies, governments, presidents, kings – all are ephemeral, all shouting into the wind of their greatness and power. Only the people remain, nurturing their goats and chickens, planting their gardens, their olives and grapes, a great river of humanity rising and falling with tides and currents, flowing on, enduring.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

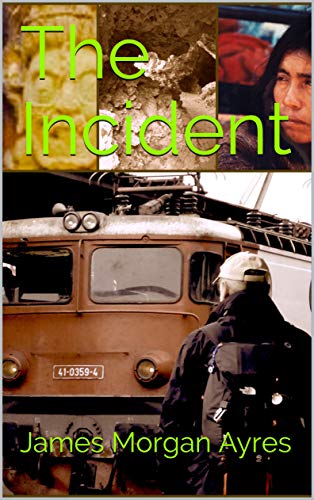

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Scott and Ra,

Thanks to both of you for your kind comments. Rendezvous in Byzantium this year?

James

Oh James,

what a journey you took me on, the layers of history, you’ve carved out a sculpture of words that is so satisfying, slakes the hunger for the “authentic”, but also stokes the fires of desire for more. I agree a “mini-documentary”!

What a wonderful article. So beautifully written, and the images that James has created out of the reality that passes across his mind and eyes are a mini documentary of which I would love to see. He should be paid by the Turkish government, big bucks, for his vision of their country. Don’t stop, don’t stop.

James, I wander over Lonely Planet forums attempting to answer questions would-be travellers have about this, the Lycian Coast of Turkey. I will be sure to point them in the direction of this commentary on life in Kaş. Thank you…

Good of you to do that Johnny. If I had corresponded with you previously I would have come here sooner.