A Fine and Quiet Season

By

Morgan Ayres

Aix en Provence is a sparkling and sophisticated city at any time of year. In summer it’s hot, sultry, intoxicating, and mobbed by tourists. In late fall and early winter Aix takes on a different character. The winds of October send the last of the tourists scuttling home, like leaves across the sidewalk in front of Deux Garçons. Serenity returns. Colors are muted. The last glory of autumn has faded but the city itself is alive and welcoming.

Morning skies are shades of grey. Soft pearl tones predominate with streaks of pewter and sometimes a hint of anthracite looming in the east. Imagine a luminescent dome over the city shot through with beams of pale sunshine, as if the city has been transported to the interior of a living pearl. Afternoons are usually graced by a brilliant china blue sky and golden light suffuses everything. Evening comes quick and sharp and small groups of people hustle through shadowed streets headed for well-lighted restaurants with fresh white tablecloths, clear wine glasses and the pop of corks. In this season Aix is the kind of place you would come to with someone you love, perhaps to celebrate an anniversary, which is what we did.

At this time of year you experience the city as the residents do, as a town of charm and grace. You can wander up Cours Mirabeau, the wide boulevard which is the heart of the city, without shouldering your way through relentless crowds. Rough barked plane trees that arch over the Cours Mirabeau and provide shade in summer still hold their leaves and now that leafy canopy shelters walkers from the occasional light shower. It’s a time for long meandering walks through cobble-stoned streets and just cold enough to send you to a heated sidewalk café after your walk for a cognac or a glass of good red to warm you while watching the life of the city.

Cafes are not crowded. People are out and about. Parents push their bundled children in strollers. Women walk briskly, shopping for dinner, or perhaps a sweater, or a pair of those stiletto heeled shoes in the window. Three red cheeked girls with short skirts and heavy sweaters laugh their way down the street, leaning on each other and making eyes at a group of young men gathered around a large silver motorcycle. A policeman balances his bicycle on the sidewalk, flirting with the salesgirls standing in the doorway of a children’s shoe store.

After a warming glass you might wander over to the tourist office where the ladies who work there lost their minds in July and were struck comatose in August as wave after endless wave of tourists assaulted their desks demanding tickets to shows, directions to Cezanne’s house, directions to the market, reservations for hotel rooms and train schedules. These ladies have now regained their senses and their charm. They smile. They cheerfully help you and chat with you about the current attractions of the city.

You might do a little shopping, as we did. The lady at the boulangerie where we bought a baguette for an afternoon picnic slips a croissant chocolat in the bag. No charge. Madame Arnot, the manager of the stationary store, welcomes us with a cheery, “Bon Jour.” Her eyes are blue, her complexion pale, her ink black hair done up in one of those Juliette Binoche coifs. She’s of a certain age, attractive and trim in her well fitting burgundy wool dress, and displaying panache with a Hermes shawl draped around her shoulders. Stunned by my execrable French, touched by my pathetic attempt to communicate and perhaps thinking I was the village idiot in my home country, she asks with some concern, thankfully in English,

“You are from where?”

“I come from a far western province of the United States,” I answered. “A place called California. Perhaps you have heard of it?”

She smiles and arches her left eyebrow. “Ah,” she says. “You come from the land of Arnold. Even down here in the country we have heard of your famous Terminator.”

After a few minutes of conversation, during which she recommends an out of the way restaurant and tells me about her sister who lives in Los Angeles, she packs up our small purchases and we go on our way, pleased by the slight but pleasant encounter.

A short walk from the Cours Mirabeau brings us to the large outdoor market, the one with the fountain where the water runs clear, and cold and tastes of iron and slate. The stall keepers wear scarves and hats. Brightly colored awnings and umbrellas, arranged side by side, cover most of the market. The sky in early afternoon is a vast vault of impossible blue, crossed by clean white clouds hurrying on their way west to the mountains.

In one of the stalls a husky, smiling man in a blue turtleneck sweater and a baseball cap, sells wonderfully pungent dry sausage made from wild boar and stuffed with garlic, wild nuts and berries gathered in the hills. One will go well with the baguette, another will keep for the train tomorrow. In the next stall a small round lady with long delicate hands offers me a slice of dry cured ham on a small white paper plate. We buy 200 grams sliced very thin. Then there is a long glass covered counter with peppercorn pate, country pate, pate with cognac, more varieties of pate than you could sample in a month. A thin slice of the peppercorn goes into our shopping bag.

In another aisle tables are loaded with squash, peppers, new potatoes, and small crisp red apples. Baskets overflow with wild mushrooms. Then an aisle of cheeses: goat cheese in twenty varieties, richly veined blue in large wheels, small rounds of soft Camembert, and Brie, and an aisle tables covered with spices, each in a separate bowl, the air scented with curry, cumin, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg. A white haired man in pressed grey flannels a black sweater and with the air and manners of a gentleman scoops lentils and beans in a dozen different varieties and colors from their baskets.

At the other end of the market we find an array of bric a brac, the contents of a hundred attics displayed on tables arranged end to end in long rows and on blankets spread on the pavement. Antique, gold-rimmed platters with hand painted hunting scenes are arranged next to silver serving platters, ivory handled carving sets, matched sets of sterling dinnerware and hundreds of mismatched forks and knives, some with horn handles, remnants of the gilded age.

Wearing warm sweaters and wool caps we sit on a green wooden bench, and make a small picnic while watching children scamper around a plaza in a residential section. With a horn-handled pocketknife I bought last summer in Thiers I slice the sausage wafer thin, cut the Brie into small pie shaped pieces and slice a crisp red apple into quarters. We debate saving the croissant chocolat until later, with me putting forth Wilde’s point of view that the only way to deal with temptation is to give in to it. But prudence prevails and we give the light chocolate roll to two of the children.

In this season there are plays, concerts, exhibits of photography and art of all kinds. But one of the best things to do in Aix is to wander the narrow streets and make your own discoveries. Find the little restaurants, the ones not in any guidebook. Get a haircut and make friends with the other patrons. Stumble across a hidden courtyard and lean inside to listen to an unseen saxophonist who, from the sound of the music, could be Dexter Gordon reincarnate. Read the signs on the bulletin boards at the Internet café and go to an informal ballet recital at a local school where you meet some of the parents and have coffee with them and talk about small things and agree to meet for dinner.

Late in the afternoon we stroll to the cozy English bookstore, where tea bubbles on the burner, scones lurk in wait for the unwary and rows of books ascend to the ceiling. We buy a couple of mysteries to read on the train and then walk along narrow streets past high stone walled buildings, back to the Hotel De France, a small unpretentious hotel, much in the style of old French hotels, the ones where long ago the bath was down the hall. Now the plumbing has been updated and although the bed sags a bit, it’s okay. It’s okay because the first time we came to France so many years ago we stayed in small inexpensive hotels like this one and staying here takes us back to that time in a way that the business hotels in which we usually stay do not.

It rains here in this lovely grey season, but the rain falls softly and doesn’t last long and leaves the air fresh and crackling with electricity and after the rain the wind is clean and the sky so clear that the distant hills seen from the window of your room tug at you. If you want to get out of town for an afternoon and the hills don’t tug hard enough to draw you, the beach towns are empty and only a short drive, a string of small sand swept villages where a few cafes and bars remain open to serve locals. You can walk for miles along beaches that were packed thigh to thigh in summer and see no one, the sea a pale peridot green tipped by restless whitecaps. A graveyard of fallen American soldiers of World War II in the nearby countryside has fresh flowers on the grave, more than fifty years after the war. If you return to Aix for dinner you might want to eat at a landmark, a restaurant in business for over a hundred years.

Dinner at Deux Garçons is a leisurely affair. The waiters are polite, attentive, and take a formal pride in their work. A large party on the other side of the room celebrates the sixteenth birthday of a radiant girl in a chic black dress, her honey blonde hair trying its best to stay piled on top of her head. The glasses of champagne the family sends to your table taste of apples, vanilla, spice and happiness. The duck is tender and rich, and the Beaujolais Nouveau, which arrived this very day, is fruity and full of sun. Someone plays a light, wandering jazz tune on a piano in another room.

The rococo interior of the restaurant, unchanged in two centuries, is reassuring. It’s gilded and green molding, its ornately edged mirrors behind the bar, its chandeliers, and paneled walls are reassuring, the white tablecloths and tinkle of silver are reassuring. The moment takes on a ceremonial quality and informs you that in troubled times, in an uncertain world, some things are constant; that there is a place where the small things matter, where tradition is preserved, where the ritual of a proper dinner is as sure as the rising of the sun.

Later in the hotel you might lean out of the window for a while and sip a cognac and watch the life of Place Augustin. Below the people come and go and you talk softly with your love and remember when you came to France on your wedding trip so many years ago and then you go to bed warm and happy and lucky that you have had another good year together and have been able to return to this lovely place.

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones

Sun, Apr 5, 2020: Killing Mr. Jones Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding

Wed, Apr 1, 2020: On Hoarding Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19

Mon, Mar 30, 2020: Masks Save Lives – Covid-19 Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse

Sun, Mar 29, 2020: Visions of Apocalypse Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter

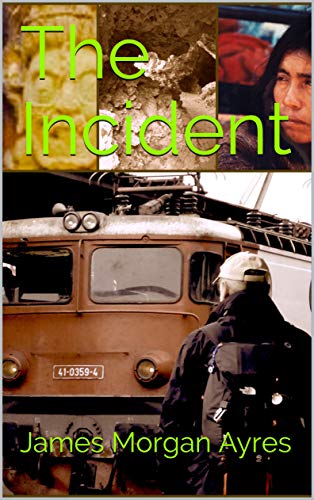

Fri, Aug 23, 2019: Hijacked Twitter Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident

Sun, Aug 18, 2019: The Incident Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End

Sat, Aug 10, 2019: Seas and Oceans Without End